Papua New Guinean masks and performance: The inner layers

The 7th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art

By Michael Kisombo

December 2012

Papua New Guinean masks and performance have a long history of development and change. In the jungle punctuated with rugged and steep mountains where the majority of Papua New Guineans live, masks were used for ritual performances and warfare. Across fast-flowing rivers and into the wetlands, these masks played a pivotal role in initiations, rituals, healing, marriage and mortuary ceremonies.

Masks and their associated performances were integrated into practising societies’ social, economic, political and religious spheres. Those men who created and wore masks were believed to be conduits for the continued presence of primordial beings, mythical ancestors and cultural heroes. They were considered special and treated with dignity and sincerity. Certain fees were imposed for the preparation of the masks and for performances, and in some areas such as the Bismarck Archipelago,1 Tumbuans2 would be sponsored by persons with special status and political position to perform.

Virtually unknown to the outside world, these astonishing societies ceased to be so isolated from the early eighteenth century onwards. With the arrival of Christianity and other cultures, many of their traditions were dramatically transformed, including those associated with masks and performances. While there was a strong impetus for change, certain mask-performing societies remained steadfast. In these places, masks and performances took on new forms and shapes but their underlying values and meaning were maintained. A layer of tradition drives some communities to uphold their extraordinary culture, as with those along the Sepik River and in the Bismarck Archipelago.3

A view of works by Vunapaka and Iatapal Cultural Groups, installed at QAG for 'No. 1 Neighbour', October 2016 / Purchased 2011. Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / © The artists / Photograph: J Ruckli, QAGOMA

Tokatokoi 2011

- VUNAPAKA CULTURAL GROUP - Creator

Tokatokoi 2011

- VUNAPAKA CULTURAL GROUP - Creator

Tokatokoi 2011

- VUNAPAKA CULTURAL GROUP - Creator

Tokatokoi 2011

- VUNAPAKA CULTURAL GROUP - Creator

Tokatokoi 2011

- VUNAPAKA CULTURAL GROUP - Creator

Tokatokoi 2011

- VUNAPAKA CULTURAL GROUP - Creator

The Middle Sepik River Iatmul-speaking people inhabit the wetlands of the Sepik plain, in villages stretching from upper Pagwi down to Tambanum and on towards Angoram.4 They maintain a rich and vibrant culture centred on their spirit houses (haus tambaran) and make a living through the sale of their art works. Among the villagers are some world-renowned carvers who have travelled overseas to share their cultural richness.5 Masks from these villages have taken on new forms with the application of synthetically derived colour and plastics for costumes and headdresses. What is intriguing is that the stories relating to these masks remain uninterrupted. These are stories inextricably tied to Iatmul mythology and religion.

During travel to this area in April 2012, welcome performances were organised for our team from the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery.6 As we entered the village square in Palembei, two men — concealed with the famous mai mask and grass-leaf skirts — approached us, dancing to the rhythm of the slit drums and flutes that sounded from their haus tambaran.7 Alongside the village square, women, children and the uninitiated lined up side-by-side to see the performances, masks and new visitors. On entering the haus tambaran, we encountered almost every man from the village who sat according to their moiety (‘fire place’), with their bare backs, arms and chests exposing crocodile ‘bites’. Four slit drums and pisin (bamboo flutes), above the house, played, producing a spectacular sound to evoke the haus tambaran’s special ancestors. Time had been taken preparing for our visit — the performance was more than simply a gesture. We sensed the presence of the evoked spirits and were taken back in time by stories and memories from long ago. After the ceremonial killing of two chickens, blood was smeared on the pisin before they were stored away and betel nut distributed among the initiates. The hidden meaning behind this ceremony is only known by the initiates.

Next we visited Yenchen, a five-minute boat ride across the mighty Sepik River. Wearing crocodile masks made from palm spathes and rattan, and led by a small group of women and children, a dance troupe welcomed us. The performance was similar to that observed in Palembei; however, in Yenchen, when such displays are presented for tourists and other visitors, they often involve a fee to assist with the upkeep of this tradition. Though this event was not as charged, they followed the ceremonial custom of smearing chicken blood on the instruments and sharing the betel nut among the men in the haus tambaran.

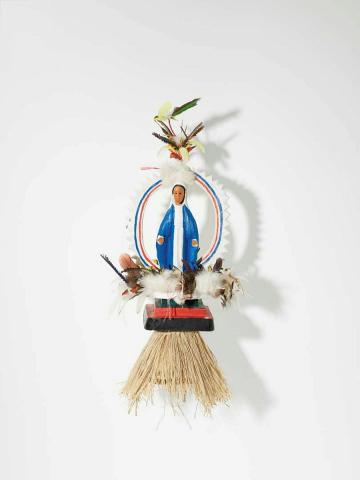

Mary 2011

- IATAPAL CULTURAL GROUP - Creator

Mary 2011

- IATAPAL CULTURAL GROUP - Creator

Mary 2011

- IATAPAL CULTURAL GROUP - Creator

Mary 2011

- IATAPAL CULTURAL GROUP - Creator

Mary 2011

- IATAPAL CULTURAL GROUP - Creator

Mary 2011

- IATAPAL CULTURAL GROUP - Creator

Akin to the Iatmul kastom, mask production and performance in the Bismarck Archipelago continues, albeit stirring much more fear, exhilaration and intrigue. This is true for anyone who attends the famous National Mask festival in Kokopo, which brings to life unique and rare masks and performances from groups across Papua New Guinea. The Tumbuans of the West and East New Britain and New Ireland Provinces, for instance, reveal a strong sense of magical power. For the Tumbuan to acquire and demonstrate that power, preparations are stringently and diligently executed. Performers, mask makers, magicians and sponsors abstain from contact with women and live on a strict diet. All preparation, including secret drills, occurs in a secluded place over two to three weeks, away from the public. During the show, Tumbuans hide inside an enclosure built close to the showground and appear accompanied by chants and songs. The host repeatedly sprays kabag (lime) on the performers to prevent attacks by the Tumbuan and other magical spells, which may spoil their ceremony. Creation stories and other mythical themes are danced by the Tumbuan, often in rapid movements as they move towards the venue’s exit. During the performance, Tumbuans are assessed by the elders with attention paid to the steps taken and their movements. When the festival ends, the Tumbuans return to their secluded place to conclude the ceremony.8

As experiences in the Sepik and the Bismarck Archipelago attest, Papua New Guinean masks and performances have transported the ancestors’ adventures from primordial mythical times and today continue their journey by taking on new forms. It is the strength of the societies’ innermost beliefs and structures that have enabled them to travel this far. Such inner layers are rooted within them and revealed through performances that hold the community together, bringing hope for a future. The masks embody the power of ancestors, gods and mythical beings invited for an occasion to officiate, with offerings such as chickens and betel nuts to send them back to their homes. The power embodied by the mask is a power that is also feared if denied or attacked. The inner layers that mask-performing societies in Papua New Guinea uphold and propagate, even in this era of modernity, hold meaning beyond the actual masks and performances.

Ule and Neo (Male and female fish) 2011

- GABUOR, Alex - Artist

- SIM, Stanley - Artist

- GABUOR, Joe - Artist

- CHUNE, Damien - Artist

- SNOWAL, Kelly - Artist

- YADEHABA, Mark - Artist

- The Bismarck Archipelago is made up of the outer islands of Papua New Guinea, including the East and West New Britain Provinces, New Ireland and Manus Provinces.

- Tumbuan is a spirit figure with a conical mask constructed with leaves and usually made of two parts; the head and the leaf skirt. Tumbuans are predominantly found in the Bismarck Archipelago and are saturated with magical power.

- I witnessed this during encounters in East New Britain, including my trip to the Sepik River and attendance at the mask festival filming performances of traditional dance and music.

- The villages found along the Middle Sepik River speak the Iatmul language and their creativity is widely documented.

- Some of the best carvers from this area have travelled to the USA, Canada, Australia, Japan and United Kingdom to construct sculptures and art works in museums, universities and art galleries. Artists from the Abelam and Kwoma groups are engaged in APT7, as mentioned by Ruth McDougall in her text.

- This travel was to film how the Iatmul play their music, on an invitation by the Director of the PNG National Museum and Art Gallery, Dr Andrew Moutu, in April 2012.

- Mai masks are made of nassa shells and decorated with white, brown and black paints. They are often mounted on a conical mask frame when used for performances. This mask is popular in the Iatmul area.

- Unfortunately I had no chance to attend a closing ceremony of Tumbuan masks. I was denied permission to film this occasion as it is believed to be made for initiates only.

Explore APT7

APT7

Dec 2012 - Apr 2013

Digital story context and navigation

Explore the story

APT7

Dec 2012 - Apr 2013