Under a Modern Sun

Art in Queensland 1930s–1950s

By Samantha Littley

Artlines | 3-2025 | August 2025

This new QAG exhibition celebrates a transformative time of creative practice, showcasing the work of leading Queensland artists and other major Australian artists working here in the mid-twentieth century. Together, writes curator Samantha Littley, their artworks present a light-filled vision of the state and, occasionally, the flipside of that picture.

Works installed for 'Under a Modern Sun', Gallery 4, QAG, August 2025 / © The artists / Photograph: N Umek, QAGOMA

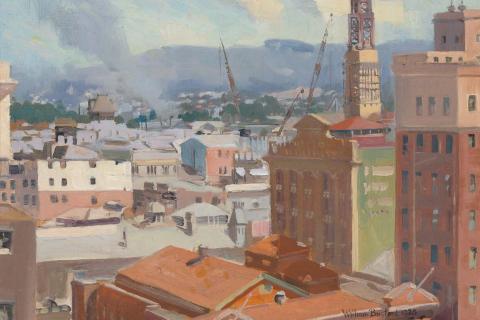

On 8 April 1930, Queensland governor Sir John Goodwin officially opened Brisbane’s City Hall, unveiling an exciting new chapter in the city’s history. The iconic structure — then the second tallest in Australia after the Sydney Harbour Bridge — immediately assumed pride of place as the state capital’s seat of civic power and a cultural hub. Crowning the edifice was Daphne Mayo’s grand sandstone tympanum, in the final stages of its completion. While anachronistic in its depiction of First Nations peoples by today’s standards, the relief remains a remarkable achievement that confirms Mayo’s status as one of Queensland’s leading sculptors.

‘Under a Modern Sun’ takes the opening of City Hall as its starting point, locating it as a marker for an age of flourishing artistic activity spurred on by this public affirmation of art’s value to the community. The exhibition spans the ensuing three decades, with the end of the era coinciding with the publication of painter Vida Lahey’s foundational text Art in Queensland 1859–1959. This period represented a vibrant phase during which Queensland’s creative landscape began to shift to accommodate fresh ideas, despite resistance from a traditional constituency.

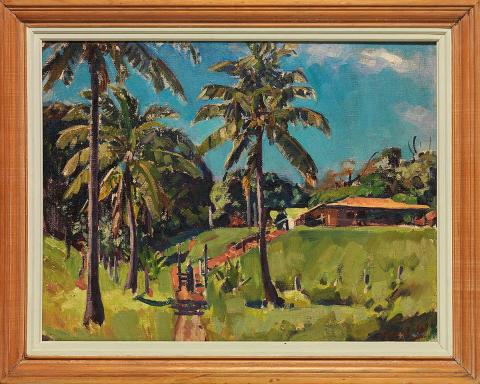

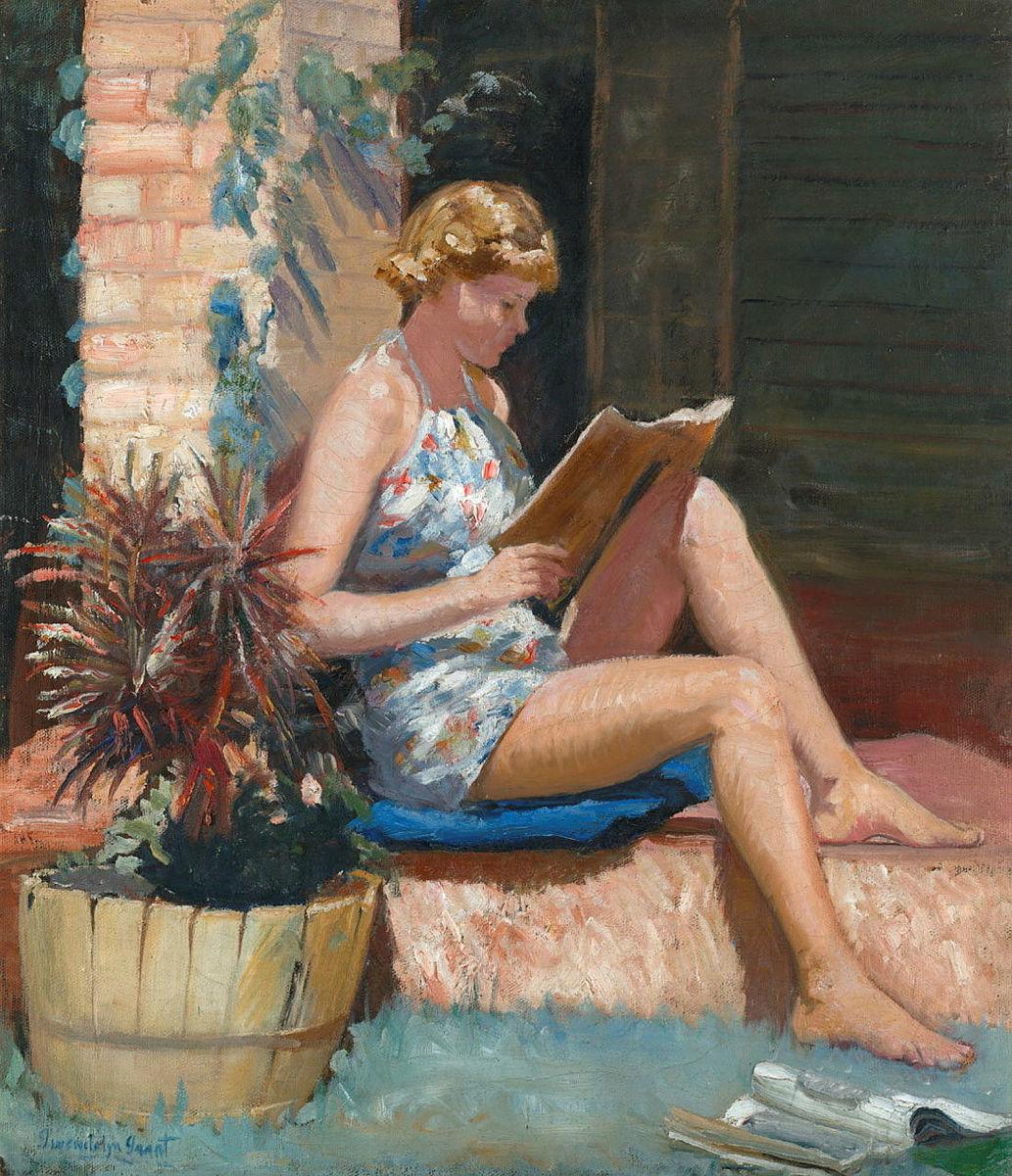

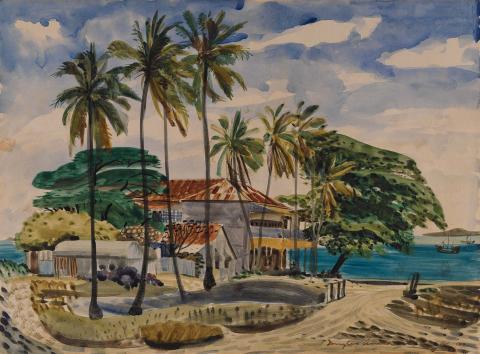

Showcasing more than 140 paintings, sculptures, photographs and works of decorative art from the QAGOMA Collection, the exhibition underscores the vital role that women artists such as Lahey and Mayo played in fostering art in Queensland, as they worked to introduce modern concepts. For example, Lahey’s waterolours of the Grey Street Bridge under construction symbolised a rapidly modernising city. Their artworks feature alongside those of their peers, including painter Gwendolyn Grant, photographer Rose Simmonds, sculptor Kathleen Shillam, and women ceramicists from the ‘Harvey School’ — one of the largest schools of art pottery in Australia in its time, founded by renowned sculptor and potter LJ Harvey.

‘Under a Modern Sun’ highlights artworks by renowned Brisbane-based painters such as William Bustard and WG Grant that spark dialogues with those by luminaries from the regions, including Kenneth Macqueen on the Darling Downs and Joe Alimindjin Rootsey (Barrow Point people, Ama Wuriingu clan), who captured the rich tones of his Country in the state’s north. The exhibition explores the connections between these artists and those from interstate who contributed to the development of a modernist sensibility here, among them Charles Blackman and Sidney Nolan. A later group of paintings by Margaret Olley and Margaret Cilento, who each returned to Brisbane from Europe in the 1950s, and by Jon Molvig, who moved to the capital in 1955 and invigorated the city’s art scene, point to the expressive directions that art in Queensland followed in succeeding years.

Gwendolyn Grant / Australia QLD 1877–1968 / Winter sunshine 1939 / Oil on canvas / Purchased 1939 / Accession No: 1:0266 / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Gwendolyn Grant Estate

1930s

In 1929, painter and critic Gwendolyn Grant observed wryly that ‘Queensland artists have yet to be infected by the so-called ‘modern art’ movement’.1 Against the backdrop of the Depression and associated hardships, established Queensland artists did adhere to a benign version of Modernism, experimenting with colour and the simplification of form rather than challenging modes of representation. Their position was unsurprising, given the resistance to change expressed within the Royal Queensland Art Society (RQAS), which, at the time, provided the main arena in which to exhibit work. For example, the decorative arts were only included in RQAS exhibitions from 1929, following the appointment of LJ Harvey as a Trustee and at the urging of influential members such as Mayo, Lahey and Bustard. Innovation in painting was similarly mistrusted. For instance, Miles Evergood’s gently experimental postimpressionist landscapes caused unease when they were shown at the Gainsborough Gallery in 1932, despite being modestly priced in deference to the economic downturn.2

Conversely, Bustard’s Summer haze 1937 — featuring an impression of Brisbane bathed in humidity — and Charles Lancaster’s A corner of Brisbane 1937 — with its simplified blocks of colour and strong treatment of light and shade — represented the acceptable face of modernism in Queensland. On the Darling Downs, Kenneth Macqueen brought a contemporary eye to the Australian landscape tradition with crisp, clear watercolours that reflected his commitment to a modernist aesthetic. And in the state’s north, South Australian-born painter Noel Wood, who moved to Bedarra Island in 1936, quickly established a reputation for his light-infused paintings, with the critic for the Cairns Post declaring that Wood had conveyed ‘the dazzling sunlight of the North as no other artist has ever succeeded in doing’.3

1940s

In Queensland, the early 1940s were marked by the social upheaval that accompanied World War Two. Brisbane’s City Hall served as ‘a hub for civil defence activities’ and the capital became host to upwards of 80,000 United States’ servicemen, while north Queensland became, in the words of official war artist Robert Emerson Curtis, ‘the frontier state in the Pacific War most vulnerable to attack’.4 Allusions to the war were scarce in exhibitions at the RQAS, causing younger artists, such as Laurence Collinson of the breakaway Miya Studio, to rail that: ‘While literally millions of starving and tortured people in Europe are breathing their last, what do we see on the walls of our local galleries? Vases of flowers’.5 The paucity of war-related artworks in this context may have been more a consequence of artists wishing to provide relief from the realities of the conflict, than a denial of its existence. In some instances, however, the war created opportunities. For example, Bustard and his Sydney-based contemporaries Douglas Annand and Max Dupain were each employed as camouflage officers for the Royal Australian Air Force. Stationed variously in North Queensland, the Torres Strait and New Guinea, their roles afforded them the chance to capture new environments.

In Brisbane, artists such as Vera Leichney continued to paint in a measured style that stood in stark contrast to the paintings of Vincent Brown, who had studied in London and was familiar with the European styles of Cubism and Fauvism. With his brilliant, non-representational use of colour and his emphasis on the underlying geometry of natural and built structures, Brown’s paintings were immediately perceived as revolutionary. More revolutionary still were the expressive paintings of Melbourne artist Sidney Nolan, who travelled to Brisbane in 1947 and embarked on a series of paintings inspired the tale of Mrs Eliza Fraser, who survived a shipwreck off K’gari (referred to as Fraser Island from 1847 until 2023) in 1836. The visceral qualities of Nolan’s paintings represented a new and stimulating aesthetic that would influence the practice of artists such as Sydney painter Charles Blackman, who saw Nolan’s artworks in Brisbane at the Moreton Galleries in 1948 and would soon form his own associations with Queensland.

Sculptors Kathleen and Leonard Shillam progressed contemporary styles in their practices after they established themselves on Brisbane’s bayside. Their work revealed the influence of British modernist Henry Moore, whose sculptures Leonard had encountered during his studies in England in the late 1930s, and which Kathleen had seen in Melbourne in 1948.6 Through their work, their support of younger artists, and the support they received from gallerists Brian and Marjorie Johnstone, the Shillams became Queensland’s most prominent sculptors.

Reclining woman 1942

- SHILLAM, Leonard - Creator

Thursday Island pub 1943

- ANNAND, Douglas - Creator

Mrs Fraser 1947

- NOLAN, Sidney - Creator

1950s

The 1950s saw significant shifts in artistic practice and appreciation in Queensland. An influential factor was the 1951 appointment of Robert Haines as director of the Queensland National Art Gallery. Haines was responsible for the Gallery’s major purchases of early modern European art, such as Pablo Picasso’s La Belle Hollandaise 1905. Moreover, the arrival in Brisbane of painters such as Blackman and Jon Molvig, the return of Margaret Cilento and Margaret Olley from overseas, and the emergence of new artistic voices, including that of watercolourist Joe Alimindjin Rootsey, enlivened visual culture in the state. A member of the Ama Wuriingu clan, Traditional Owners of the lands around Barrow Point in north Queensland’s Cape Melville National Park, Rootsey had worked for decades as a stockman and knew the route linking Laura, Lakeland and Cooktown intimately. While he was hospitalised in Cairns in 1954 with the tuberculosis that would eventually end his life, Rootsey’s skill as an artist came to the attention of medical social worker Joan Innes Reid, who became an advocate for his art. The following year, Rootsey’s work featured in the Royal Queensland Show, and in the Cairns Show in 1957. Two years on, his paintings of Country — informed by a deep, personal knowledge — were shown alongside works by other significant Queensland artists, including Kenneth Macqueen and Olley, at the Caltex Centenary Art Competition held in Brisbane’s City Hall.

At the conclusion of Vida’s Lahey’s survey Art in Queensland 1859–1959, she remarked on the ‘static ideas of the past and the kaleidoscopic changes at present’. Her comment was perceptive, given the developments that occurred in the last three decades of this period. Advances were stimulated by public works that generated a sense of civic pride, and by the work of artists committed to contemporary practice. Through their efforts, art in Queensland advanced steadily through the 1930s and 1940s, with new ideas from Europe gradually finding acceptance; and then more rapidly in the 1950s. Significantly, the late 1950s saw broader recognition of Indigenous Australian artists through the work of painters like Joe Rootsey, whose artworks stand as testament to the resilience of his people. Through this multiplicity of voices, art in Queensland was enriched and expanded and continued to diversify over the coming decades.

Harvesting scene c.1956

- MACQUEEN, Kenneth - Creator

(Kalpower) c.1959

- ROOTSEY, Joe - Creator

Blue-eyed daisies 1959

- LAHEY, Vida - Creator

Samantha Littley is Curator, Australian Art. This is an edited adaptation of Samantha’s curatorial essay ‘Modernism comes to Queensland’, featured in the exhibition’s accompanying publication, which is proudly supported by the Gordon Darling Foundation.

- Gwendolyn Grant, from an unattributed press clipping dated 1929, quoted in Keith Bradbury and Glenn R Cooke, Thorns and Petals: 100 Years of the Royal Queensland Art Society, Royal Queensland Art Society, Brisbane, 1988, p.76.

- Keith Bradbury and Glenn R Cooke, p.81.

- ‘Tropic North Presented in Art’, Cairns Post, Cairns, 10 December 1940, p.9.

- See Kylie Hadfield, ‘A road trip through wartime Queensland’, RSL Queensland, Brisbane, 3 August 2002, https://rslqld.org/news/latest-news/aroadtrip- through-wartime-queensland, viewed January 2025; and Robert Emerson Curtis, quoted in Michele Helmrich and Ross Searle, ‘The canvas of war’, Defending the North: Queensland in the Pacific War [exhibition catalogue], University Art Museum, University of Queensland, Brisbane, 2005, unpaginated.

- Laurence Collinson, quoted in Bradbury and Cooke, p.88.

- Stephen Rainbird, Breaking New Ground: Brisbane Women Artists of the Mid Twentieth Century [exhibition catalogue], Queensland University of Technology (QUT) Art Museum, Brisbane, 2007, p.57.

'Under a Modern Sun'

Aug 2025 - Jan 2026

Digital story context and navigation

Explore the story

'Under a Modern Sun'

Aug 2025 - Jan 2026

Related resources