VALE: Remembering MacPherson

By Chris Saines

Artlines | 1-2022 | | Editor: Stephanie Kennard

Australia lost one of its most vital, inquiring minds with the passing of Robert MacPherson in November of 2021. Here, QAGOMA’s Director, Chris Saines CNZM, gives tribute to the career of an artist who spent a lifetime unfolding the endless complexity of seemingly simple ideas.

With the passing of Robert MacPherson at the age of 84 on 12 November, Australia lost one of the most important artists of his generation. MacPherson translated the often-arcane languages of conceptual and minimalist art into images and objects that formed a reply to everyday life. His work was grounded in a deep family connection to the land and his history as a cane field worker, a ringer, and a ships painter and docker. Though his work commands immense respect in the contemporary art community, his contribution to broader visual culture deserves to be more well known. In a career spanning 50 years, he exhibited across Australia, in the Sharjah Biennial in the United Arab Emirates and in Lisbon, The Hague, Berlin, Sao Paolo and Singapore. He is extensively represented in Australian state gallery collections, including here in Queensland.

Robert MacPherson, September 2016 / Photograph: Mark Sherwood, QAGOMA

QAGOMA presented a career-spanning survey of MacPherson’s work, ‘The Painter’s Reach’, in 2015. The exhibition drew together the disparate strands of his interests, revealing an artist who spent his lifetime attending to notionally simple ideas, unfolding their endless complexity and potential for artistic enquiry. ‘The Painter’s Reach’ revealed an artist who unfolded the endless complexity of seemingly simple ideas; he was fascinated with systems of all kinds, whether drawing on art and social history, or the natural world and its taxonomies. His work was grounded in his biography: driven by a deep family connection to the land and his history as a cane field worker, a ringer, and a ship painter and docker. For MacPherson, art and life were inextricably joined.

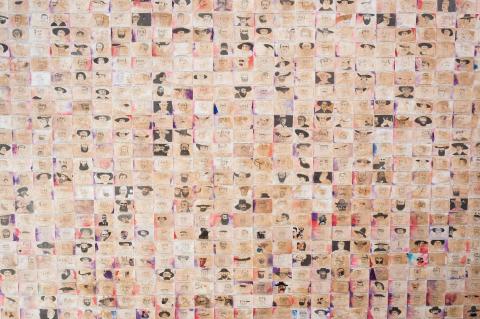

‘The Painter’s Reach’ featured one of MacPherson’s greatest achievements, 1000 Frog Poems: 1000 Boss Drovers (‘Yellow Leaf Falling’) For H.S. 1996–2014. Now proudly in the QAGOMA Collection, it is a monumental series of 2400 ink and pencil portraits that pay tribute to the legendary men and women who drove cattle along the stock routes of Australia’s east coast. They are drawn under MacPherson’s alter ego as ten-year-old student Robert Pene (and dated 14 February 1947, MacPherson’s tenth birthday), and the resulting vast mosaic is a work of brilliant archival research and artistic vision. Its epic presence amplifies the artist’s love of humble, hard-working outback life.

Mayfair: (Swamp rats) Ninety-seven signs for C.P., J.P., B.W., G.W. & R.W. 1994–95 installed for 'The Painter's Reach', with 1000 BOSS DROVERS... 1996–2014 (detail) seen at far left, GOMA, July 2015 / All works © Estate of Robert MacPherson / Photograph: Brad Wagner, QAGOMA

Equally idiosyncratic to MacPherson’s approach is Mayfair: (Swamp Rats) Ninety-Seven Signs for C.P., J.P., B.W., G.W. & R.W. 1994–95. It taps into the hand-painted blackboard roadside signs that appear along our regional highways – the white-on-masonite words that alert us to the block ice and bait to be found 250 metres down the road. This poetic and playful exploration of the amateur sign-maker’s art is a source of cultural knowledge on Australian idiom and shows a deep affection for language.

Robert MacPherson lived and made art in Brisbane for five decades. He received an honorary Doctorate from Griffith University in 1995 and was made a Member of the Order of Australia in 2020. In 2015, he was recognised as a Queensland Great and honoured for his formative role in Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art. It can be all too easy to overlook a rigorous and serious artist whose work requires our close attention but refuses to seduce it. Robert MacPherson pursued his artistic practice with a certainty and sense of purpose beyond critical and public recognition. Now that we have lost him, it’s time we looked again at what he left behind.