Watercolour in Queensland 1850s–1980s

Watercolour features in the earliest records of European exploration and settlement of Australia. Its continuous presence in the history of Queensland art has changed and evolved with shifts in culture, as well as with the demands and innovations of its practitioners. ‘Transparent: Watercolour in Queensland 1850s–1980s’ explores the breadth and diversity of watercolours held in the Gallery’s Collection, and demonstrates the medium’s important role in Queensland’s visual history — from the colonial era to the early to mid twentieth century, to an intense period of creativity in the 1960s and 1970s and into the 1980s, which was arguably watercolour’s most exuberant and expressionistic decade.

Watercolour was most often the medium of choice in documenting the early years of European settlement. As the nineteenth century progressed and as the colony grew, a dialogue developed between a lively group of semi-naive artists and the emerging professional ranks of artists and teachers. At this time, artists also began to look overseas for inspiration, travelling to Europe to study and, in turn, encouraging the dissemination of modernist art and ideas back home in Queensland.

The immediacy and vibrancy of watercolour gave it new impetus during World War Two, where its relative economy and transportability made it ideal for the rapid sketching of impressions. Following the war, a local school of Expressionism explored the medium to create unique personal visions, further demonstrating watercolour’s great potential.

For more than 150 years, watercolour painting has enlivened artistic life in Queensland. In ‘Transparent’, this is revealed in the considerable achievements of Queensland’s watercolour artists, who occupy a significant place in Australian art history.

A new confidence

The years following World War Two saw the emergence of a local school of Expressionism, which used watercolour expertly in the creation of unique visions. One of the most important watercolour painters of the late 1940s, WG Grant (1876–1951) came to the medium relatively late in his career, when it became difficult to secure oil paints during the war. Grant’s watercolours are characterised by free brushwork and vibrant colour, stimulated by the Queensland light.

In the 1950s, another unique expression of watercolour emerged in the work of Aboriginal artist Joe Rootsey (1918–63). While Grant’s art focused on Brisbane and its environs, Rootsey’s was based firmly in his country around Barrow Point and Cooktown in north Queensland, and represented the powerful connection of Indigenous Australians with the land.

The expressive strain of the 1950s was propelled by Margaret Cilento (1923–2006), but was most fully realised in the 1960s in the freely executed watercolours of Joy Roggenkamp (1928–99), whose work explored an acute interest in nature. Encouraged by her teacher, painter Jon Molvig, Roggenkamp developed a technique, which, although it appeared deceptively simple, demonstrated an exemplary handling of this difficult medium. Roggenkamp’s work inspired other artists working with watercolour, including Robyn Mountcastle (b.1936) and Thomas Pilgrim (1927–2004), to evoke their own highly personal visions of Queensland, its light and atmosphere.

The modern and the decorative

While the early twentieth century saw the rise and rapid dissemination of modern art and ideas worldwide, traditional styles lingered in Queensland, as seen in the pensive watercolours of Toowoomba-born artist JJ Hilder (1881–1916). Some Australian artists looked overseas for inspiration, travelling to Europe to study and often staying for long periods. Ipswich-born artist Bessie Gibson (1868–1961) was one, settling in France in 1906 and not returning to Brisbane until 1947. Artists like Gibson used the medium to record impressions of their travels, just as an earlier generation of British watercolourists had responded to their experiences of Australia.

Bold or reduced colour palettes and simple forms were the hallmarks of the work of Vida Lahey (1882–1968) and Kenneth Macqueen (1897–1960), who were the outstanding modern watercolour practitioners in Queensland in the 1930s and 1940s. Both used the medium expertly and almost exclusively, achieving national reputations as a result.

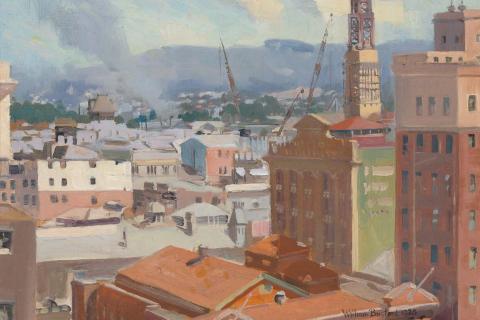

Lesser known, but nonetheless skilled, watercolourists included William Bustard (1894–1973), Roy Parkinson (1901–45) and FW Potts (1888–1970). Bustard, a trained stained-glass artist, used watercolour for the cartoons of his designs, later developing his skills to capture expressive land and seascapes. Parkinson, too, was known for his animated seascapes, while Potts, who was a farmer like Macqueen, painted scenes from near his farm at Flaxton on the Blackall Range.

The nineteenth century: A truthful register

Watercolour was most often the medium of choice for documenting the early years of European settlement in Australia, chosen for its ability to record fine detail and favoured for its portability and convenience. Together with drawing, watercolour was the logical choice for the first artistic works by Europeans of Australian subjects and, accordingly, its practitioners were often military officers, explorers and professional artists accompanying expeditions. Its qualities were most admirably expressed in the work of Conrad Martens (1801–78), who travelled to the Darling Downs in the early 1850s.

Some 30 years later, the works produced by Harriet Jane Neville-Rolfe (1850–1928) in the early 1880s tell a new story. Neville-Rolfe’s paintings were produced on Alpha Station in central Queensland, and were largely of the local Aboriginal people and the native flora and fauna, as well as life on the land. Although these watercolour sketches were never intended for public viewing, they are important and enduring social documents, which originally functioned as ‘snapshots’ of life in the colony for family back in England.

As the colony grew, a new group of self-trained artists emerged. Naive in style, their impressions captured the lives of the smaller landowners and celebrated a burgeoning civic pride. The colony’s rapid development attracted the interest of numerous artists, including CGS Hirst (c.1826–90) and Oscar Friström (1856–1918), who used watercolour to render aspects of daily life in the new towns and emerging cities. They noted the new prosperity to be earned by working the land in Queensland, expressed in the ordered abundance of the fruits of hard work. Hirst and Friström, and other itinerant artists from this era, may have lacked some degree of technical skill, but their creative output has greatly enriched the state’s visual history.

A nurturing environment

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, as the infrastructure of the colony of Queensland improved and Brisbane began to acquire facilities usually found in much larger cities, formal institutions for teaching and education were established. The Brisbane School of Arts opened in 1881, the Royal Queensland Art Society opened in 1887 (as a result of the efforts of artists Isaac Walter Jenner, Oscar Friström and LWK Wirth), and the Queensland National Art Gallery opened its doors in premises in Queen Street in 1895, following advocacy by Jenner and R Godfrey Rivers.

The emerging teaching system attracted artists like Rivers (1858–1925), who started teaching in Brisbane in 1891, and FJ Martyn Roberts (1871–1963), who began in 1894; between them they taught in Brisbane for over 40 years. Artists also began to seek out the company of fellow practitioners and enthusiasts, with informal groups and newly formed clubs meeting to discuss, appreciate and practise art in a convivial atmosphere, which, in turn, nurtured individual talent and expertise.

Watercolour was an ideal medium for these artist–teachers to perfect their own skills, and students were encouraged to exploit its versatility in capturing fine detail and evoking atmosphere. This training often engendered an intense appreciation of watercolour, as can be seen in the early works of Vida Lahey. As a student of Rivers, Lahey developed her artistic skills through watercolour in order to depict the expanding city of Brisbane in the early twentieth century.

Wartime challenges

Watercolour’s immediacy and vibrancy led to a surge of interest during World War Two — its transportability made it ideal for the swift sketching of impressions in the field. Often stationed in remote locations with few art materials at hand, artists in the armed forces turned to watercolour and sketchbooks, as they were easily carried and more readily available than oil paints and canvas.

North Queensland, in particular, was at the forefront of Pacific military activity at this time. Douglas Annand (1903–76) was engaged as a camouflage artist with the Royal Australian Air Force (1941–44); James Wieneke (1906–81) served with the 2nd AIF (Australian Imperial Force) Royal Australian Engineers (1942–46); and Douglas Green (1921–2002), who was in the Royal Australian Survey Corps, produced contour maps from both photographs and on-site expeditions as part of a unit largely based on the Atherton Tableland.

Paradoxically, creativity and innovation flourished during the war years. Stationed in remote places for extended periods, these artists endured long and isolated leisure hours, which they filled with art making, often experimenting with new modes of expression.

Explore ‘Transparent: Watercolour in Queensland 1850s–1980s’

Digital story context and navigation

Explore the story