Painters' Paintings: Flesh and light

By David Burnett

Artlines | 1-2011 | March 2011

The term, ‘a painter’s painter’ is one that invokes a particular and specific relationship between that which one painter recognises and identifies in another’s work. The term captures a particular recognition of materials and processes that is not always evident to a ‘lay’ viewer. It is, to a degree, a little hermetic in that it is predicated on the assumption that painters deal with a language that is infamously fugitive and mutable. Many artists, particularly modernist painters have addressed the inadequacy of discourse to effectively define the moments, the accidents and the intentions of painting — of manipulating pigment on a surface — its capriciousness and its inimitable qualities as a medium for representation and expression.

Chaim Soutine and Willem de Kooning emerge from distinctly different historical, social and geographical frameworks, but they share an engagement with materials, actions and processes that in almost all respects are complicit in the same objective. The singular nexus that unites them is their process, which draws on a dynamic relationship between execution, mark-making and image. Their working method relies on rapid execution, intuition, impulsiveness and a certain abandonment of conscious control of the image.

As modern painting consciously, and often dramatically, unfolded in Paris during the early years of the twentieth century, it took on an unprecedented vitality and urgency that challenged and eventually dissolved many of the conventions and traditions of nineteenth-century painting. Life displaced history as the major subject for many modern painters and the genres of still life, portraiture and landscape painting were transformed beyond their accepted parameters.

Chaim Soutine was born in the tiny village of Smilovitchi in Lithuania in 1893. He arrived in Paris at the age of 20 and was drawn to the art of the past in the Louvre where he saw the work of Titian, Tintoretto, El Greco, Goya, Rembrandt and Courbet. He was also open to the rapidly evolving work of modern painters such as Van Gogh, Bonnard, and Cézanne. Soutine met Jacques Lipchitz and Amedeo Modigliani in Paris with whom he maintained a strong friendship until the latter’s death in 1920. He was largely based in Paris from 1925–29 but his earlier periods of work in the southern French towns of Céret and Cagnes produced some of the artist’s most memorable portraits and landscapes which were to have a lasting impression and influence on a later generation of painters when they were shown in America from the mid-1930s to the late 1950s.

Soutine’s early phases of work in Céret and Cagnes are most emphatically drawn from the landscape and people of these small villages. He moved to the Pyrenees mountain village of Céret in 1919 with the support of the dealer, Léopold Zborowski, to whom Modigliani had introduced Soutine in 1916. Over a three year period, he produced landscapes and portraits characterised by a sense of intensity and exhilaration born of direct and almost visceral experience of his subjects. Forms were distorted, splayed, expanded and painted in high-key hues in which the chthonic energy of the earth and the palpable flesh of his sitters were brought to an almost feverish level of expression. Soutine returned to Paris in 1922 with over two hundred canvases, many of which were destroyed as he came to reject the Céret period. In 1923, the American collector, Albert C Barnes purchased a large number of Soutine’s works in Paris, contributing to the artist’s wider recognition and financial security.

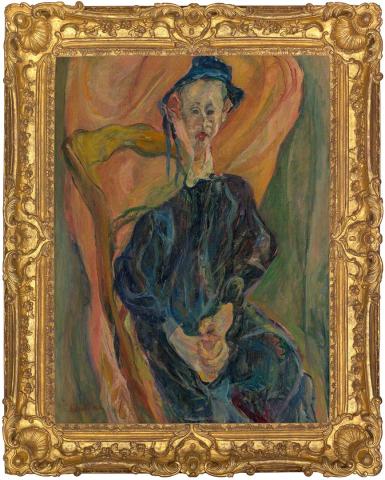

L'homme aux rubans (Man with ribbons) 1921–22 is concurrent with the artist’s Céret period, but its precise place of execution is yet to be confirmed. The work is characterised by a fluid distortion of the figure typical of Soutine’s portraits of the period. The curvilinear construction of the work contributes to an overall integrity of the painting which also typified his landscapes of the period. This ‘all-over’ treatment is a result of Soutine’s process which at the time, consisted of immersing himself in the life of the subject whether it was the landscape or a portrait. It was vitally important that the energy of the subject was available to the artist — the motif had to be present. Upon his return to Paris, this direct engagement with the motif became less urgent. Soutine absorbed himself in the art of the past as avant-garde developments such as Dada and Surrealism emerged from which he remained entirely aloof. Rembrandt, Chardin and Courbet became increasingly important to him as he sought to inflect his subjects with a greater sense of traditional design.

Albert Barnes’s purchase of over 50 of Soutine’s works in Paris and his promotion of him in the United States raised the artist’s profile and popularity at a time when the New York School of expressionist abstraction was emerging. Soutine’s works were included in Alfred Barr’s 1930 exhibition, Painting in Paris from American Collections at the Museum of Modern Art. Further one-man shows followed during the 1930s and his reputation reached its apogee in 1950 with a posthumous retrospective at MoMA when Abstract Expressionism was at its zenith as the pre-eminent avant-garde movement in America. Soutine’s death in 1943 and much of the romantic mythology which surrounded him contributed significantly to the importance of Soutine to a number of the New York School painters including Jackson Pollock and the Dutch-born, Willem De Kooning.

Klaus Kertess writes that Willem De Kooning’s series of ‘women’ paintings from the late 1940s and early 1950s, and their attendant risk of chaos were, ‘in part empowered by the paintings of Chaim Soutine’ and that Soutine’s, ‘ability to unite the expressive urgency of the acts of his making with the subjects of those acts’ as providing De Kooning and others of his generation with, ‘a strong model, in their quest to retrieve and reinvent painterly opticality’.1 De Kooning has acknowledged Soutine as his favourite painter, stating that, ‘He builds up a surface that looks like a material, like a substance. There’s a kind of transfiguration, a certain fleshiness in his work . . . I remember when I first saw the Soutines in the Barnes collection . . . the Matisses had a light of their own, but the Soutines had a glow that came from within the paintings - it was another kind of light’.2

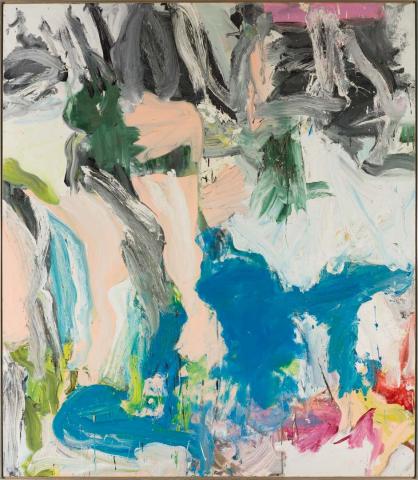

It was light and nature that were the catalysts for a series of paintings De Kooning completed between 1975 and 1980. He purchased a house in Springs, East Hampton on Long Island in 1961 and by 1963 had built a large studio, but it was not until the mid 1970s that he embarked on the series of large abstract landscapes of which, Two trees on Mary Street . . . Amen! is one. De Kooning had an abiding relationship to light and water, born of his Dutch childhood in Rotterdam, an echo of which was present in the low topography and Atlantic light of East Hampton. At the age of 71, De Kooning commenced a body of large format works that re-engaged with earth, sky, light and water in a fresh and inspired manner, not entirely dissimilar to Soutine’s immersion in the colour and light in the hills and landscapes of Céret and Cagnes. Bernhard Mendes Bürgi describes them as, ‘not abstractions of the experience of nature; they are abstract in following an uncurbed energy principle without beginning and end, allowing things to emerge, to rise to the surface in analogy to nature’.3 The Gallery’s Two trees on Mary Street . . . Amen! 1975 supports the claims made for this series of paintings as De Kooning’s most important body of work, together with his ‘Women’ series of the 1950s. For both Soutine and De Kooning, painting was intrinsic to their lives and their works are testaments to their deep and uncompromising involvement with painting as an act of creative affirmation.

This is an edited version of 'Painters' Paintings: Flesh and light', the tenth and final article in a series focusing on selected works from the Queensland Art Gallery’s international collection.

Endnotes

- Klaus Kertess, ’Painting’s skin’, De Kooning. Paintings 1960–1980 [exhibition catalogue], Kunstmuseum, Basel, 2005, p.48.

- Willem de Kooning, quoted in Maurice Tuchman and Esti Dunow, The impact of Chaim Soutine (1893–1943): De Kooning, Pollock, Dubuffet, Bacon, Galerie Gmurzynska, 2002, p. 53.

- Bernhard Mendes Bürgi, ‘Abstract landscapes’, De Kooning. Paintings 1960–1980, Kunstmuseum, Basel, 2005, p. 24.