A sculptural response: Picasso's Vollard Suite

By Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow

Artlines | 1-2018 | March 2018

Until mid-April 2018, QAG hosts the National Gallery of Australia exhibition ‘Picasso: The Vollard Suite’. As Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow writes, the themes and questions raised by the famous suite — to which the dynamics between artist and muse, and men and women, are central — can be further explored through selected sculptures from the Collection.

He spoke to her, he stroked her

Lightly to feel her living aura

Soft as down over her whiteness.

His fingers gripped her hard

To feel flesh yield under the pressure

That half wanted to bruise her

Into a proof of life, and half did not

Want to hurt or mar or least of all

Find her the solid ivory he had made her.1

In the story of Pygmalion, the sculptor falls in love with his creation. He wishes her to life with his touch, wanting to feel the softness of living flesh rather than the hard materials he has worked into a mere semblance of a human form. He is enthralled by her perfection — perhaps as profoundly as he is impressed his own talents and artistry. Ego, the animating potential of a sensual touch — a still subject brought alive. What greater power exists?

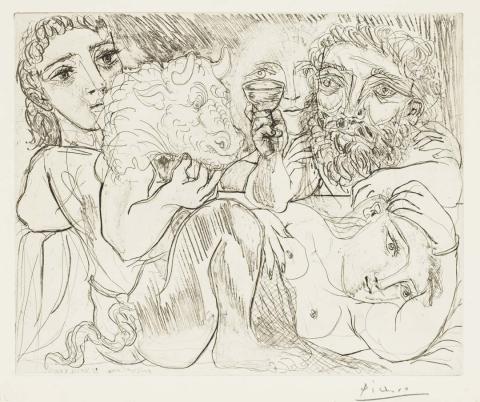

Picasso finds all he needs to reflect on his own life in classical mythology. In the ‘Vollard Suite’, the energy of Picasso’s relationship with his young muse, model and lover — Marie-Thérèse Walter — is channelled into 100 images. Of these, 46 focus on the sculptor’s studio and are languid, sensual and playful. Other works reveal darker drives and desires, and feature the mythical half-man, half-animal Minotaur. The distinctive features of Marie-Thérèse, who was 17 when she met the 45-year-old artist, are also found across the suite in images exploring intimacy, vulnerability, sexuality and violence. Picasso's own features are clearly recognisable in only one print; however, the suite as a whole can be seen as an extended self-portrait and includes images of surprising honesty.

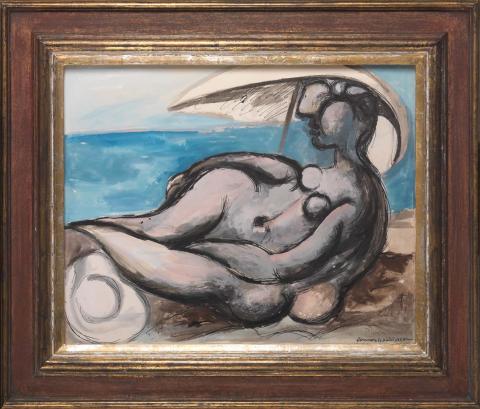

Until 15 April 2018, Queensland audiences are able to explore this iconic group of works on loan from the National Gallery of Australia, presented together with our own blue-toned gouache of the same period, Femme au parasol couchée sur la plage (Woman with parasol on the beach) 1933. The woman we see reclining here is described in a series of curving forms, her nose arches almost to her forehead, a feature we see also across the 'Vollard Suite', where Picasso describes and often accentuates Marie-Thérèse‘s prominent aquiline nose in different ways. We see a very similar play of forms in Picasso’s sculptures of the period, some of which can are reproduced in a photo essay published in the first edition of the surrealist magazine Minotaur, shown as a part of the exhibition, and available electronically in the gallery.

The creative process of making sculpture is key to the ‘Vollard Suite’, as well as the relationship between men and women in both art and broader cultural histories. We have selected key sculptures from the Collection to further explore these themes – both in the context of artistic tradition, and in terms of Picasso’s influence on later generations of artists. Italian artist Giacomo Ginotti’s nineteenth-century white marble Lucretia presents the idealised figure of a woman at a moment of absolute trauma. According to Roman legend, she was raped, and we see her poised to take her own life as a result.

Also on display are classically influenced works by Australian artists — Daphne Mayo’s bronze figure of a woman Susannah 1942 (cast 1980) and Raynor Hoff’s delicate plaster The Kiss 1924. Later works include Joel Elenberg’s two bronzes titled Anna, both cast in 1979, which record his wife’s features. Like Picasso, Elenberg finds beauty and drama in his partner’s profile. Contemporary artist Mike Parr’s Stepped wedge 1998 radically interrupts the space of the gallery, its wax and graphite surface echoing the physicality of Picasso’s mark-marking. A powerful presence, Parr’s work dramatises the rush of two lines converging on a distant vanishing point.

Picasso created the prints of the 'Vollard Suite' at a time of upheaval in Europe. Fascism was on the rise. Only months after he completed the final three prints, portraits of his patron and the commissioner of the suite Ambroise Vollard, Picasso painted Guernica, using much of the same iconography to protest the bombing of civilians in his Spanish homeland. We recognise the distinctive profile of Marie-Thérèse Walter, together with the bull and the wounded horse. Soon after, the unexpected death of Vollard in a car accident and the upheaval of the Second World War delayed release of the prints. When they were published in the 1950s, the art historian Hans Bollinger gave the works descriptive titles, nominating five groupings: ‘The Plates’, ‘The Battle of Love’, ‘Rembrandt’, ‘The Sculptor’s Studio’, ‘The Minotaur’, ‘The Blind Minotaur’ and ‘Portraits of Ambroise Vollard’.

We have opted to show the prints in these groups, rather than in date order, for instance. If we were to do so, it would be clearer that Picasso created the suite in bursts, often working quite quickly drawing directly onto the plate, with distinctive ease and beauty of line. We see this in the classically derived images of ‘The Sculptors Studio’ as well as the poignant ‘Dying Minotaur’. Mortally wounded, the man/beast is watched over by the repeated face of Marie-Thérèse. Picasso shows his capacity as a printmaker, gouging into the metal surface of the plate to create ‘Minotaur caressing a sleeping woman’, a remarkable image of tenderness, together with potential violence. Sometimes he returns to certain images reworking the plates again and again. Amongst these are two of the five titled ‘rape’ by Bollinger. We can understand his reasoning as we distinguish the bearded figure of a man overcoming a woman, perhaps. Her head arched back. Is this a moment of suffering or abandon? Each iteration of the image is marked by a muscular circular churning of limbs and melded bodies. Is this in fact an image of shared energy, and physicality, not only domination.

Picasso’s ‘Vollard Suite’ offers a rich reflection on the artist’s intimate world in all its complexity — and raises questions around the relationship between men and women, the ideals and narratives we convey through art and story-telling, power and beauty. Subjects we continue to grapple with today.

'Picasso: The Vollard Suite' is a National Gallery of Australia Exhibition. See it in Gallery 4, QAG, until 15 April 2018.

Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow is Curatorial Manager, International Art, QAGOMA.

Endnotes

- Drawn from Ted Hughes’s ‘Pygmalion’, in Tales from Ovid (Faber and Faber, London, 1997). My thanks to my colleague David Burnett, Curator, International Art, for introducing me to this evocative translation.

Connected objects

The Kiss 1924

- HOFF, Rayner - Creator

Lucretia 19th century

- GINOTTI, Giacomo - Creator

Anna cast 1979

- ELENBERG, Joel - Creator

Anna cast 1979

- ELENBERG, Joel - Creator

Homer cast 19th century

- UNKNOWN - Creator

Stepped wedge 1998

- PARR, Mike - Creator

Monument cast 1970

- MIRÓ, Joan - Creator

Susannah 1946, cast 1995

- MAYO, Daphne - Creator

Related artists

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject