Nusra Latif Qureshi: Justified behavioural sketch

Nusra Latif Qureshi's ruminations on the feminine form are drawn from the rich literary and visual traditions of south Asia. Her delight in painting these figures is revealed in the subtle and sensual handling of detail. The graceful gesture of hands, the polished sheen of pearl earrings and bead necklaces, the fall and curl of locks of hair, and the folds of cloth around each figure recall motifs from classical paintings of the Mughal, Rajastani and Pahari Schools of north India.1 Qureshi's paintings take pleasure in focusing on the female subject — early works such as Afterthoughts 2001 are semi-autobiographical, and more recent works reference the love stories of the Punjab and Sind regions.2 Qureshi's protagonists are lone figures in reverie, often entwined and interlaced with the sinuous forms of leaves and fruits, and sometimes with the ghostly figure of a lover.

In each of Qureshi's paintings, the range of imagery is composed as a series of layers, with the central female subject painted in complete, flawless detail. These refined figures, often citing a precedent from a Mughal illuminated manuscript of the sixteenth century, are the only part of the paintings depicted in full. Surrounding each figure are various outlines drawn from colonial photography from northern India, botanical drawings, stencils and wallpaper patterns by William Morris (of Morris & Co.) or textile patterns from the Ottoman and Persian empires. These sources are usually illustrated as silhouettes, fragments or outlines, or filled with a single vibrant colour in which the suppression of detail adds to the overall complexity of composition. Qureshi's recent paintings are filled with an abundance of botanical imagery from the Company School, and the foliage forms an ethereal web of lines around the central figure that accentuates an earthy sensuality.3 The addition of the silhouette of a mechanical instrument or tool such as a microscope disrupts these paintings, hinting that there is no single narration. The implication is that these paintings are also visual conundrums that offer an opportunity for an open ended interpretation, dependent on the history and knowledge of each viewer.

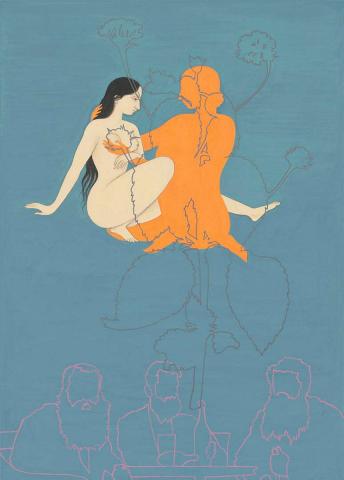

The painting Justified behavioural sketch depicts a woman with long black hair, wearing a white salwar kameez and sitting on a platform. Layered on this image are the outlines of several men dressed to play polo. This cut-out sketch taken from a photograph refers to another important cultural sphere — the imperial game of polo. Originating in Persia (now Iran) around 600 BCE, polo was popular with kings and courtiers of the Mughal and Rajput courts of India. During colonial times, the sport was avidly adopted by the British. The British also commandeered the skills of the miniature painters of the courts to create astonishing albums of the flora and fauna encountered in the subcontinent. Instructed to paint a single species on each page without contextual landscapes, court painters made exacting, free-floating images. Justified behavioural sketch pictures these distinct Indian traditions — polo and the Mughal miniature. Both remain an inherent part of the cultural history of the subcontinent. In the painting Qureshi uses this history to develop her own taxonomy of images. The figure of a woman poised in reflection, contemplation and concentration is the anchor point at the heart of Qureshi's work in QAGOMA's Collection. The poetic figure of the female heroine is also central to the mystical verse by the renowned Sindhi poet and saint Shah Abdul Latif (1689-1752), one of a group of Muslim poets to innovate the mystical Islamic Sufi tradition using the popular love stories of Hindu north India.

It is the female heroine with whom the poet exclusively identifies, and whose stories invariably include the endurance of ordeals, trials and journeys to arrive at a place of transformation where she may attain the object of her desire. The adoption of the feminine voice by Shah Abdul Latif was common to medieval Indian poets but contrary to the customary usage in the Sufi literary tradition of the Middle East. By adopting this Indian device and using the concept of the central feminine voice, Shah Abdul Latif immortalises these verses in the ecstatic Sufi tradition. Thus, the folk heroines of Risalo personify all the varied facets of love and desire in the context of Islamic esoteric forms, and invariably these heroines find themselves to be alone. This is not to say that they are lonely, rather they become figures that epitomise and embody love. These are some of the interests captured by Qureshi's exquisite paintings — Gardens of desire II 2002, A garden of fruit trees 2006 and My sister in the garden of wonders 2006, for example. They depict a female heroine who is an active, corporeal personification of love, not a passive receiver.

Endnotes

- The classical Mughal, Rajastani and Pahari Schools of north India each had their own distinct painting styles. Before the sixteenth century, Muslim courts in India employed Persian emigres and locals who struggled to imitate the style of their masters. The Imperial Mughul painting workshops of the sixteenth century were the most complex in organisation and were recognised as producing some of India's most celebrated paintings. Other regional courts established painting workshops in Rajasthan and in the Punjab hills; centres such as Kangra, Basholi, Guler and Mandi subsequently developed their own painting styles.

- Punjab is a northern Indian province and Sind province, which today forms part of Pakistan. Both were once part of the Indian, Mughal and British Empires until partition in 1947.

- The term 'Company School' refers to a disparate collection of drawings, watercolours and paintings on paper, mica, glass, ivory and shell produced during the period when the British East India Company expanded to south Asia from the early seventeenth century to the mid-nineteenth. Company School paintings were created by Indian court painters specifically for British tastes and are often defined as an observation of all aspects of colonial India, including natural history, historical architectural sites and contemporary life.

Connected objects

Afterthoughts 2001

- QURESHI, Nusra Latif - Creator

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject