ESSAY: Ozawa’s ‘Vegetable weapons’

By Reuben Keehan

‘We Can Make Another Future’ September 2014

Together with Makoto Aida, Tsuyoshi Ozawa is one of the most prominent artists of the younger generation of University of Tokyo graduates, who helped reinvigorate the capital’s art scene in the mid 1990s. He made perhaps the most famous and abiding contribution to Masato Nakamura’s ‘Ginburart’ project of 1993 with his portable Nasubi Gallery, a Japanese milk crate offered as an exhibition space, its name (meaning ‘eggplant’) an anagrammatic play on the name of the prestigious rental gallery Nabisu, outside of which it was initially located. In 1991, Ozawa developed a collaborative creative approach that he dubbed sodan bijutsu (‘consultation art’), paralleling participatory practices elsewhere known as ‘relational art’, ‘social practice’ and ‘kontext kunst’. This spirit of dialogue extended to a playful internationalism, posing questions of identity, cultural provenance and Japan’s place in Asia and the wider world. Adroitly and with great humour, Ozawa also produces work as part of the comedic pan-East Asian artist collective Xijing Men.1

For his works entitled Museum of Soy Sauce Art 1998–2000, Ozawa used the culturally loaded medium of soy sauce to create parodies of historical and contemporary Japanese masterpieces. These works were displayed in a recreated museum, complete with wall texts, wax ‘historical’ figures and implements supposedly used in the creation of these ‘masterpieces’. Replicas of artworks from the Kamakura (1185–1333) and Momoyama (1573–1615) periods were placed alongside meticulous reconstructions in soy sauce of the work of avant-garde artists of the postwar period, such as Yayoi Kusama, On Kawara and Lee Ufan. By creating a fictitious history of soy sauce art, Ozawa offered a humorous challenge to the authority of the museum and art history, satirising Western stereotypes of Japanese culture at the same time as problematising Japan’s assimilation of the European canon. The first work in a series of shoyu hanga (soy sauce prints) produced in 2006, Soy sauce print: Altamira Cave + Marcel Duchamp encapsulates this parodic tension with recognisable motifs drawn from Paleolithic cave paintings and Marcel Duchamp’s seminal artwork The Large Glass 1915–23, which are superimposed onto a Japanese scroll.

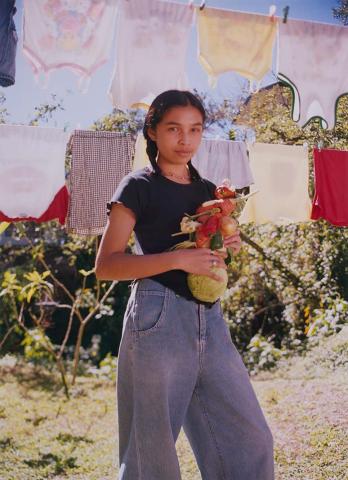

Arguably, Ozawa’s most representative body of work is the photographic series ‘Vegetable weapon’, which has been an ongoing project since 2001. In every city Ozawa visits, he invites women to cook their favourite meal from the region in which they live. The essence of this project is grounded in the act of sharing a meal, the vegetables and condiments of which are assembled into model weapons. Each participant is photographed with their creation and the ingredients provide the food for the party that follows; the photographs are carefully framed with the weapon held poised as if ready to fire. Ozawa has found that initiating conversation through the consumption of food, devised as a weapon of destruction, uniquely demonstrates the need for perspective in understanding the process of conflict. Moreover, each meal is particular to the culinary expertise of the different cultures or communities.

In the ‘Vegetable weapon’ series, it is women who hold these parodies of war, which is a deliberate decision by Tsuyoshi Ozawa to highlight the assumption of gender specificity in contemporary conflict. It hints at a range of associations, from the commodification and consumption of the female body in commercial photography — especially when brandishing a phallic object — to the psychoanalytic relationship between ingestion and carnal possession. That a desiring gaze and a gendered subject are present in works dealing with local manifestations of Asian cultural identity suggests that the body — particularly the female body — is a battlefield as significant as those on which more conventional weapons are deployed.

Endnote

- Initiated in 2006, Xijing Men is a collaboration between Ozawa, Chen Shaoxiong (China) and Gimhongsok (Korea) based on the cultural and diplomatic expressions of the fictitious, itinerant city of Xijing, whose name, meaning ‘Western capital’, makes it a counterpart of Beijing (northern capital), Nanjing (southern capital) and Tokyo (eastern capital).

Connected objects

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject