3D imaging at QAGOMA

By Nicholas Umek, Thomas Renn

March 2024

| Editor: Zenobia Frost

As part of QAGOMA’s Digital Transformation Initiative, the Gallery’s photography team often collaborates with conservators, coders and designers in its quest to make the Collection available to everyone. Recently, Nicholas Umek (Senior Photographer) and Thomas Renn (Digital 3D and Motion Designer) used the process of photogrammetry to create a 3D model of Fred Embrey’s century-old figurative sculpture — one of only three known works in its genre. Here, they discuss the impact 3D imaging has on improving the way we understand, care for and represent artworks, with benefits for conservators, academics and the public.

QAGOMA Collection Online Photographer Mark Sherwood prepares Fred Embrey's Djan’djari figure c.1930 for photogrammetric capture, QAGOMA, January 2024 / Photograph: N Umek, QAGOMA

Thomas Renn | Photogrammetry is a process of creating a 3D model by taking a lot of photos of the subject, typically working in rings around it. We use software to identify points of interest — say, an interesting little scratch — and cross-reference that scratch across all the different photos. By seeing how much this point of interest moves relative to other points in each photo, we can guess its 3D position. This happens over and over again, from all angles and orientations, until we create a little cloud of points in space. We can use these to build a 3D geometric mesh — ideally, a perfect replica of an object in 3D space.

Nicholas Umek | It’s a bit like papier-mâché, really, except we’re using images to clad this hollow geometry. It’s almost like an animal pelt that we’re cladding over a sort of weird digital taxidermy.

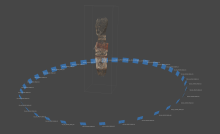

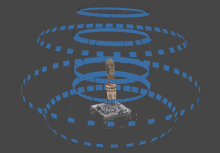

In-progress ‘point cloud’ renderings of the Embrey sculpture, showing a single ring of photos (left) and a complete dataset of seven rings of photos (right) / Images: T Renn © QAGOMA

Thomas Renn | I should mention that the photographic part is a bit different to your everyday creative photography. It’s a very precise, scientific way of capturing something, to the point where what's captured is not even described as a set of photos, but a ‘dataset’. That’s what the process is: capturing data. We work in rings around the object to ensure we get good coverage.

Nicholas Umek | For the Fred Embrey sculpture, I think we took 32 images per revolution, across seven revolutions — before we even got to the feathers.

Thomas Renn | The Embrey work has a very matte texture, so it’s fantastic for us to capture — except for the feathers. Feathers are translucent, not to mention soft and fluffy; they move if you even so much as breathe on them! For most of the photos, I just let them go every which way. Then we did a very close-up hemisphere of photos with no movement. From memory, Mark [Sherwood, QAGOMA Collection Online photographer] took around 260 photos of just the feathers.

(l–r) A photograph of Embrey’s sculpture shows the emu-feather pendant in detail, GOMA, January 2024 / The Djan’djari figure’s emu-feather pendant — highlighted here in orange on the 3D rendering — was captured in a separate dataset to the sculpture itself / Photographs: N Umek © QAGOMA

Nicholas Umek | The feathers on the Embrey work are a good example of problem-solving: we could photograph the overall object without much consideration for the feathers, and then Thomas could integrate a separate, more specific capture of the feathers into the overall model.

Thomas Renn | We can usually turn a solid object on its side or upside-down — whatever we need . . .

Nicholas Umek | But with artworks, there are often limitations on what we can do in terms of photography. At the moment, we’re working on a pot from Hermannsburg; the Conservation team will tell us what’s possible — as in, ‘You can’t sit this artwork on its head’ or ‘This part is fragile’, and so on.

Fred Embrey’s sculpture on a turntable in order to capture it from every possible angle, QAGOMA, January 2024 / Photograph: N Umek © QAGOMA

Thomas Renn | A lot is automated, but there is manual labour involved in patching up anything we couldn’t capture accurately. In the case of the Embrey work, there was a shiny stand that held it up. Because of specular highlights [the way light bounces off shiny objects], the stand was largely removed just by its failure to be captured in photogrammetry. But then I had to go in and paint out its shadow as well.

Nicholas Umek | Shall we mention for the reader your new supercomputer?

Thomas Renn | So, I’m now working on what looks like a small UFO — a computer with a very powerful GPU [graphics processing unit]. It even lights up when it goes heavy on processing.

Nicholas Umek | It used to take up to 48 hours to process a small dataset, but Thomas is now doing that in a couple of hours.

Thomas Renn | Even half an hour, with better fidelity than before. It is blazingly fast. My previous workstation was roughly equivalent to a good gaming PC.

Nicholas Umek | When we think about photographing an artwork, we’re really rendering a 3D object in a two-dimensional form; there’s always a disparity between a photo and the human experience of viewing the real thing. I think 3D representations offer new ways to experience art. Photogrammetry and laser scanning are two common tools used to create a 3D asset for a video game or movie. In those instances, accuracy of geometry (shape), colour and tone aren’t paramount, whereas we’re aiming to create as rich an experience of an artwork as possible. The Smithsonian [Institution in the United States], for instance, has been working to represent a lot of its collection in 3D online, but also to use those 3D models as a tool to help repatriate huge swathes of their collection, consulting with First Nations communities to create meaningful digital and physical replicas that support traditional customs and ceremony.

A 3D rendering of Fred Embrey’s sculpture visits GOMA’s level three via an augmented reality app in development at QAGOMA / Photograph: T Renn © QAGOMA

Nicholas Umek | While QAGOMA is barely ever closed, some of these objects can be very difficult to get to people. I often think about where I can steal ideas from: medical technology, manufacturing, engineering, archaeology. Thomas has his new computer and new ideas. It’s been fantastic trying out methods with the Embrey sculpture that we haven’t tried before.

Thomas Renn | Thinking back to the ‘Quilty’ exhibition [GOMA, 2019] — I had been filming Ben [Quilty] in his studio, and he wanted kids to be able to come into the Children’s Art Centre space and experience the thick, gloopy texture of his [impasto] oil paintings. For the safety of both the children and the artworks, we of course couldn’t use real paintings, so I proposed we scan his works with photogrammetry, right there in his studio.

For the ‘Quilty’ exhibition held at GOMA in 2019, visitors were invited to touch 3D replicas of Ben Quilty’s textured impasto artworks, June 2019 / Photograph: N Harth © QAGOMA

Thomas Renn | We made these great big tactile replicas [of Quilty's paintings] carved out of acrylic. It was so successful that we now create similar experiences whenever we can.

Nicholas Umek | I’m of the belief that the collections of public institutions such as QAGOMA belong to the people; 3D imaging like this offers us new ways to democratise access to our Collection.

Explore QAGOMA’s 3D model of Djan'djari figure c.1930.

QAGOMA Foundation gratefully acknowledges the generous support of donors to this project through the Unlock the Collection campaign.

This text is based on interviews with Nicholas Umek (Senior Photographer) and Thomas Renn (Digital 3D and Motion Designer), conducted by Zenobia Frost (Assistant Editor, Digital) on 21 February 2024

Djan'djari figure 1930s

- EMBREY, Fred - Creator