‘Impress of the eye’

Colonial period (1859–1901)

By Michael Hawker

‘150 Years: Photography in Queensland’ June 2009

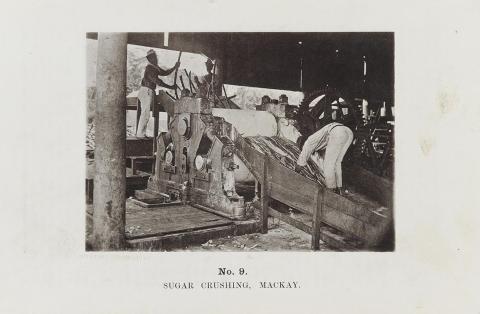

With the invention of the albumen print in the 1850s, photographers were able to create high-quality images in large quantities, and at affordable prices, for the first time. This development coincided with the separation of the new colony of Queensland from New South Wales in 1859, and as the end of the century approached, photography played a more significant role in Queensland’s social and cultural life. Scientists were using it to discover, record and categorise the natural world, while government officials were using it to document and publicise the material results of their policies. The demand for photography was met by an increasing number of professional photographers throughout the state, whose services were also sought by an increasingly image-conscious population.

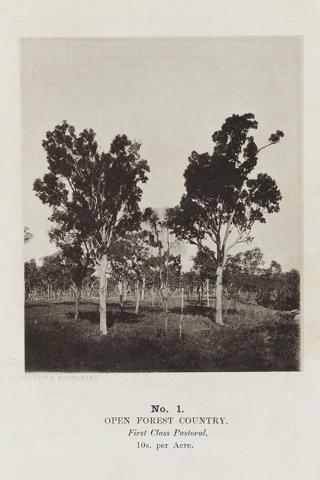

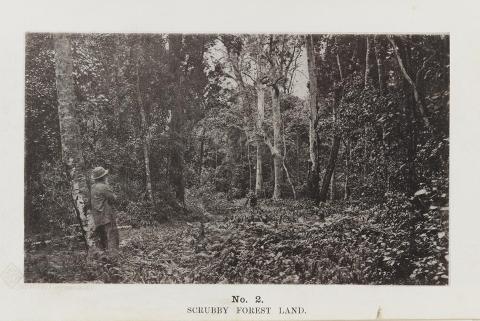

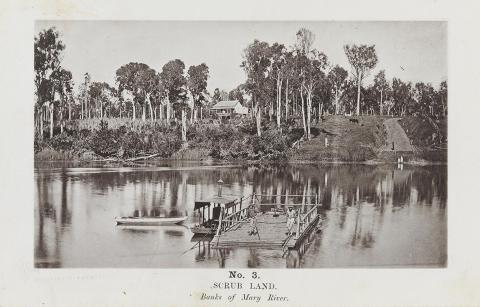

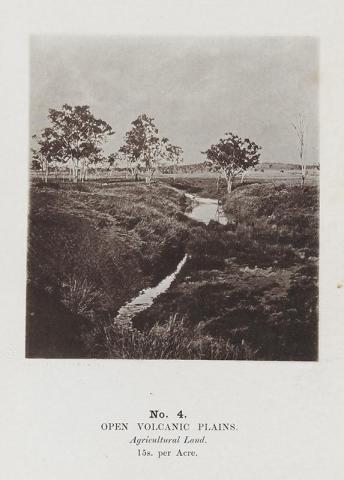

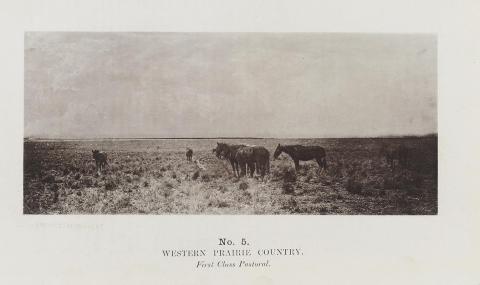

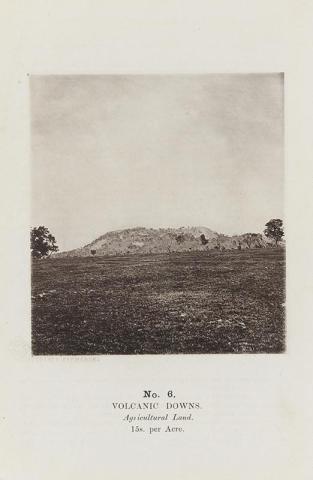

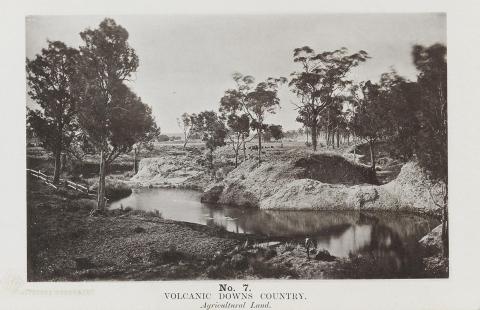

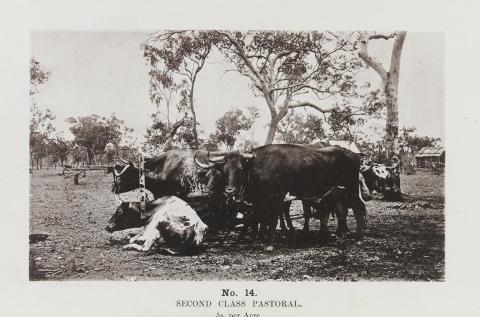

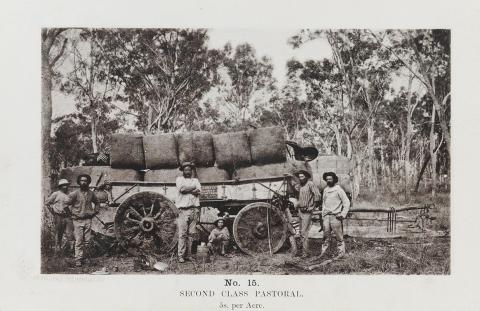

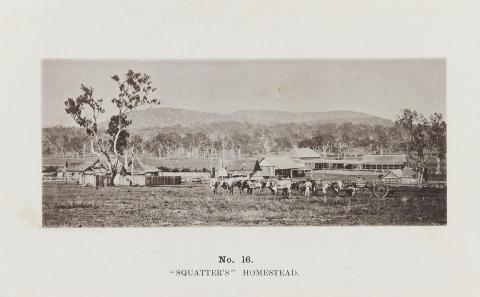

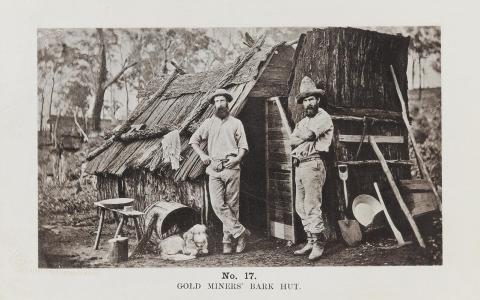

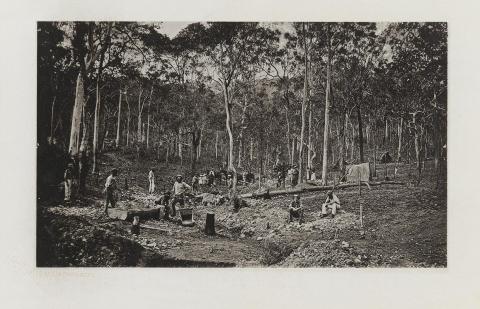

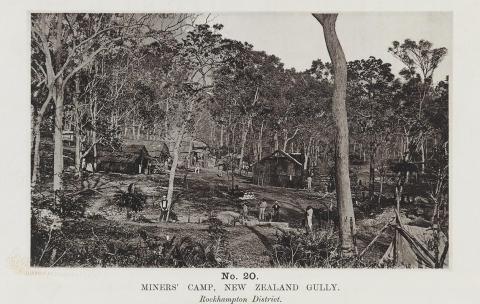

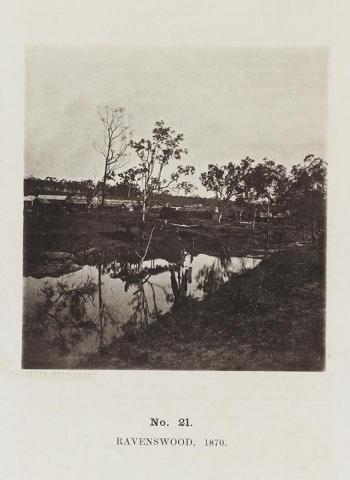

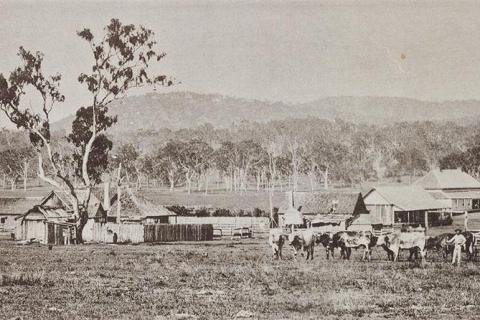

One of the finest, earliest depictions of Queensland and its people is the work of Richard Daintree. Moving to Queensland in 1864, Daintree ran pastoral properties, explored new territory from a geological perspective, and indulged his interest in photography. In 1868, he was appointed geologist in charge of the survey of North Queensland. Three years later, in 1871, Queensland was invited to participate in the London International Exhibition, and Daintree proposed an exhibit combining his geological specimens and photographs. The colonies used these international exhibitions to draw immigrants and investment. Daintree’s images provided the young colony with a unique presentation of its desirable features, in agreeance with his opinion that ‘the impress of the eye’1 through photography would appeal to Queensland’s potential investors more than would writing on the subject.

The Sydney Mail of 6 July 1872 praised Daintree’s exhibits, saying they were ‘of greatest interest to intending settlers and are closely studied by a class of men and women that Queensland would be all the better for numbering amongst its inhabitants’. The writer lamented that other Australian colonies had not taken advantage of ‘so effective and cheap a mode of making known the advantages they have to offer to hundreds of thousands of Europeans who are constantly seeking new homes and new fields of investment for their capital’.2 With economic expansion an imperative for the new colony, photography was wise to depict not only a scenic view or an aid to scientific study, but also the land as an investment, something to be bought and sold.

The development of the carte-de-visite in the later half of the nineteenth century — examples of which are featured in the exhibition — made photography a more democratic medium. Being the size of a modern business card, these photographs became popular and were exchanged between friends and visitors. Albums for the collection and display of cards became a common fixture in late nineteenth-century homes. These inexpensively produced photographs provided large numbers of people, from virtually all strata of society, with the first opportunity in history to own images of themselves and of loved ones. The sense of directness and connection that the photographic image provided was important in new, decentralised colonies such as Queensland, where many people were great distances from family and friends.

- G Bolton, Richard Daintree: A Photographic Memoir, Jacaranda Press, in association with the Australian National University, Brisbane, 1965, p.23. To the then Queensland Minister for Works on 17 April 1876, Daintree wrote: ‘My confirmed opinion is that the impress of the eye, by means of systematised pictorial illustration and tangible material record of our own resources combined, will do more to find favour in the opinion of the emigrant and capitalist than the writing of very many books and even than very many lectures’.

- Anne-Marie Willis, Picturing Australia: A History of Photography, Angus and Robertson, North Ryde, NSW, 1988, p.92.