Curating abstraction

Living Patterns: Contemporary Australian Abstraction

‘Living Patterns’ brings together 35 contemporary Australian artists whose practices include abstraction. Here, curator Ellie Buttrose takes us on a tour of the many ways abstract techniques can communicate ideas of selfhood, power and vulnerability, historical perception, complex politics and more. In using concealment or minimalism — or working within liminal and negative spaces — artists can say the unsayable.

An installation view of ‘Living Patterns’, featuring Kate Bohunnis’s an active accumulation (tense) 2020/23 and works from Johnny Niesche’s 'Schein blossom' series, QAG, September 2023 / © The artists / Photograph: N Umek, QAGOMA

The idea for ‘Living Patterns’ came about in response to a recent resurgence of artists looking at histories of abstraction — in particular, how First Nations practices make abstraction unique in an Australian context. The exhibition draws together emerging and established artists, each of whom brings different approaches and histories to their contemporary practice. Placing these artworks together in the gallery space isn’t intended to relegate them to a single idea; rather, ‘Living Patterns’ shows that there are many reasons why artists use reduction and obfuscation in their practice. Moreover, the exhibition explores the artists motivations’ to represent the unrepresentable.

While many of the artists in ‘Living Patterns’ explore common ideas — spiritual geometry, protection of customary knowledge, limits of perception, the body, labour, and the influence of nature — there are no strict thematic sections in the exhibition. Instead, there is porosity: themes bleed into one another and welcome different interpretations.

To spend time on subtleties, as these artists have, has political implications — they run counter, for instance, to the attention-grabbing headlines and violent imagery of the contemporary news cycle. For this reason, the artworks in ‘Living Patterns’ are a provocation to the viewer: the more effort you put into the viewing experience, the more nuance you will discover.

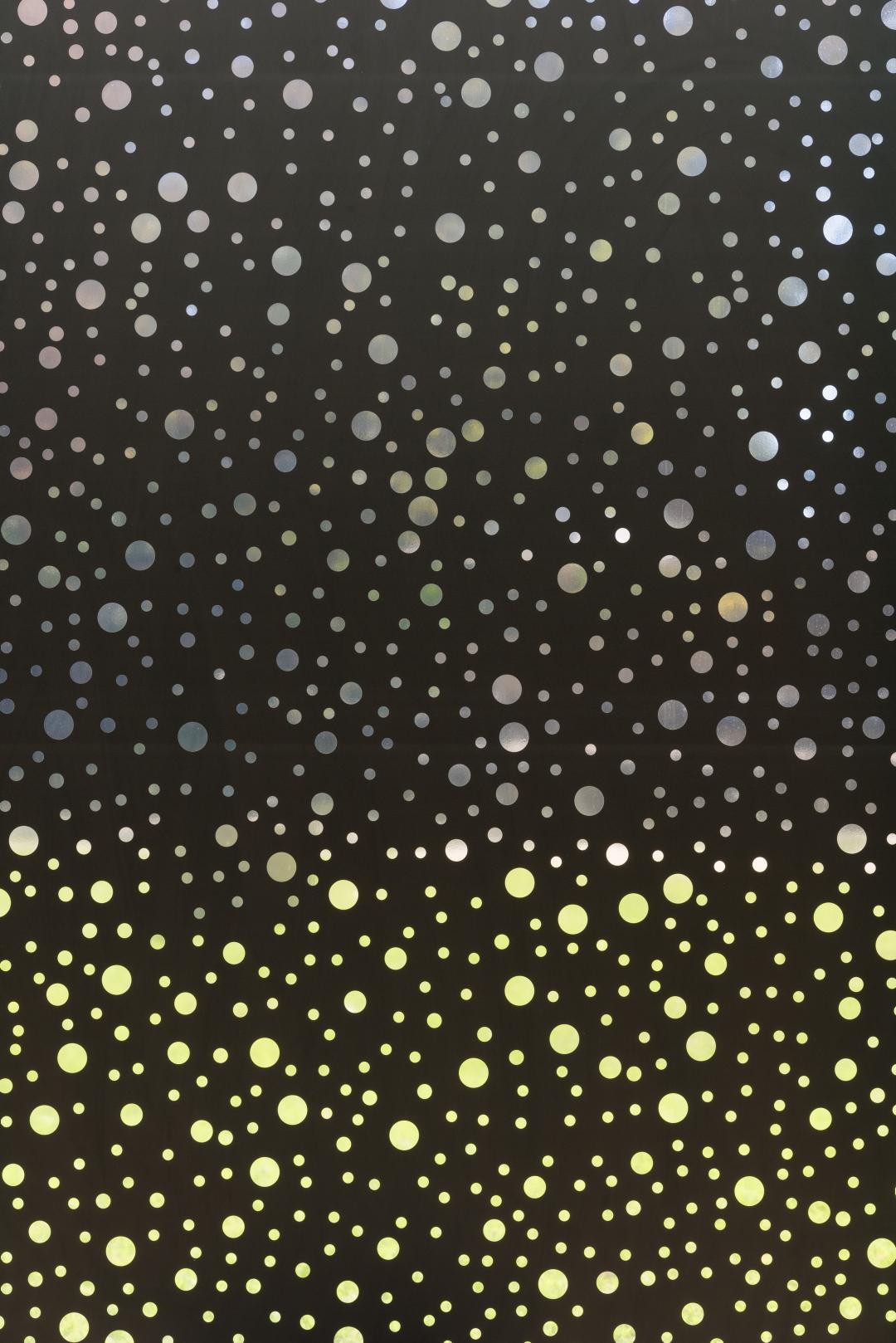

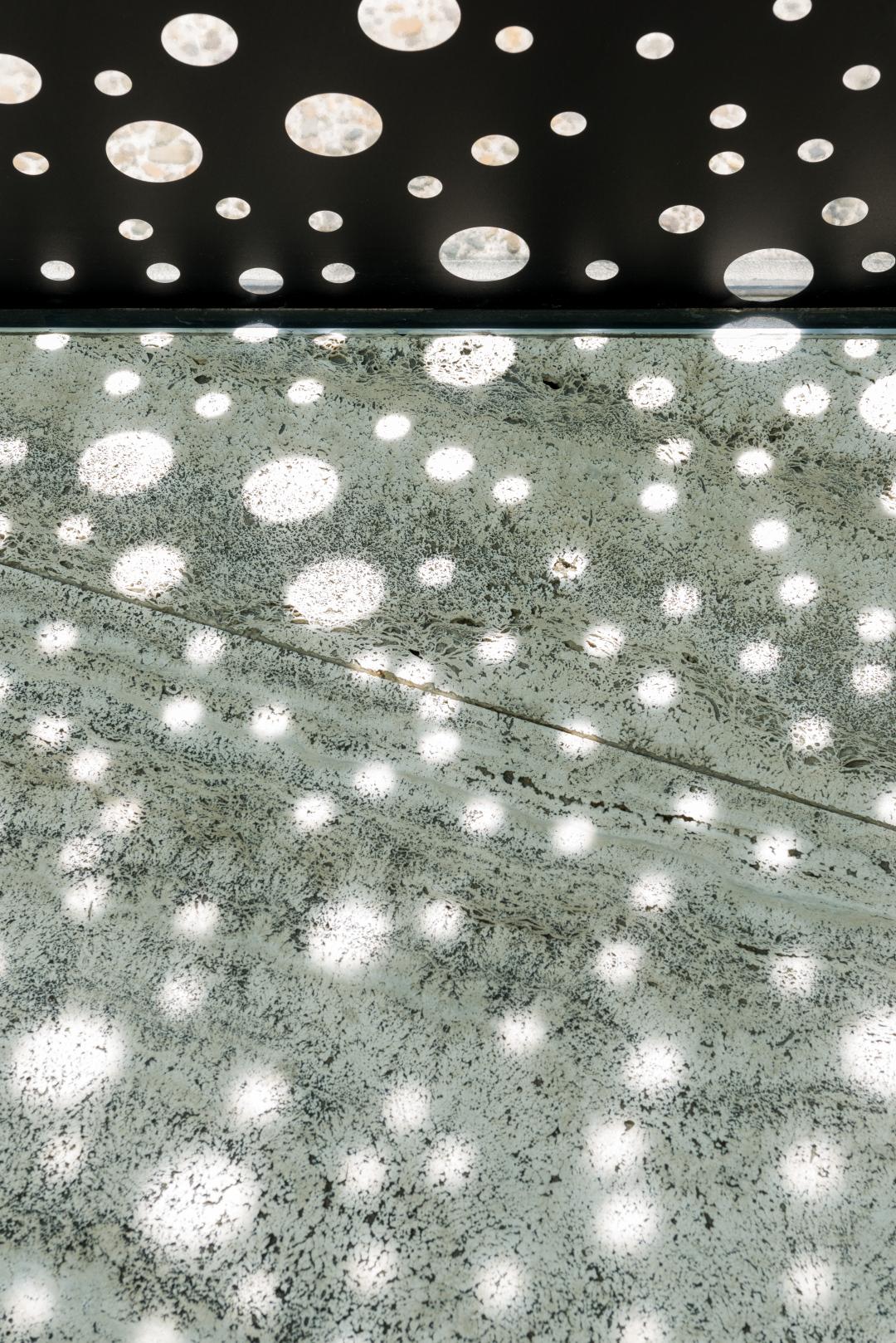

Views of Daniel Boyd’s Untitled (-27.4721524, 153.0181102) 2023, installed for ‘Living Patterns’, September 2023 / Courtesy: The artist, Sydney, and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney / © Daniel Boyd / Photographs: C Callistemon, QAGOMA

Visitors are likely to first encounter Daniel Boyd’s immersive, black vinyl window treatment — a site-specific work at QAG’s Gibson Entrance, near Stanley Place. Perforated by clear circles, Untitled (-27.4721524, 153.0181102) 2023 functions as a visual metaphor for the lenses through which we perceive the world. Adjacent is the artist’s 2017 painting Untitled (HNDFWMIAFN), which renders, at large scale, an historic image of labourers in Queensland. Grappling with the indenture of Indigenous and Pacific workers, Boyd partially obscures the image to illustrate the ‘blind spots’ that enable such injustices.

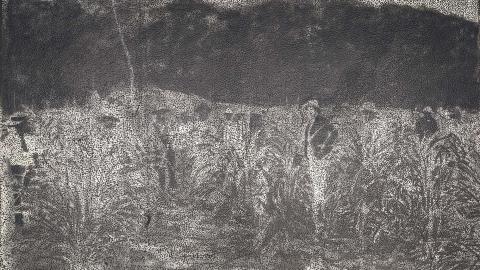

Vernon Ah Kee’s Unwritten #1–5 2017 comes at this theme from the other direction: figures push against a scrim of sharp charcoal marks. Ah Kee considers objectification as a kind of abstraction, representative of the way Indigenous peoples have been dehumanised throughout history. He cites, as some of the clearest examples, that Australia was colonised under the falsehood of terra nullius and, prior to 1967, that First Nations people were not counted in the Australian census. Where a single legible image cannot possibly account for the brutal histories Ah Kee and Boyd seek to address, these artists use obfuscation. In a roundabout way, abstraction is better able to convey the vastness of scale of these issues.

Reko Rennie evokes an image of an urban warrior in Untitled #I (from ‘ALWAYS’ series) 2018. His Kamilaroi shield-shaped canvas, painted with a fluorescent blue and black camouflage design, makes a link between historical and contemporary warriors. It refences the hip-hop trend of wearing camouflage on city streets, which — rather than concealing — actively draws attention to the wearer. Jemima Wyman’s Aggregate Icon (Kaleidoscopic Catchment) 2014 explores a similar idea; in the work, individuals wearing brightly coloured, tie-dyed camouflage are subsumed into a mass, while their eye-catching fashions draw attention to scale of the collective. In this way, artists might choose techniques of abstraction as a form of resistance.

Kate Bohunnis introduces their latex work an active accumulation (tense) 2020/23 on a ‘Living Patterns’ tour, QAG, September 2023 / Courtesy: The artist and STATION, Melbourne/Sydney / © Kate Bohunnis / Photograph: C Sanders, QAGOMA

Other artists allude to the slippery and uncontainable aspects of bodies. In Me in my tomb de-LUXE 2019, partial glimpses of figures are visible through strata of paint, which John Spiteri layers to create this ethereal composition on canvas. Working with malleable materials, Kate Bohunnis places latex under tension in an active accumulation (tense) 2020/23, as if the skin-like object is being pulled in both directions at once. d harding often references their own body — whether the reach of their arm, their height or eyeline — as a measure for their artworks. They constructed Moonda and The Shame Fella 2018 using their height as a guide for the length of glass. These artworks subtly evoke the human form, yet resist identifiable images of bodies.

Taking another approach, Tyza Hart uses white painting boards — which lean and bend around the gallery space — to engage with the history of minimalism through a queer lens. For You move (on the other side of) 2017, Spence Messih uses steel — a material aligned with both masculinity and minimalism through histories of industry and fabrication, and through the work of artists such as Richard Serra and Carl Andre — and adds testosterone gel to its surfaces. Messih has physically kinked the plates of steel, showing how a rigid material still holds the possibility of transformation.

Spence Messih introduces their steel work You move (on the other side of) 2017 on a ‘Living Patterns’ tour, QAG, September 2023 / Courtesy: The artist and Alaska Project / © Spence Messih / Photograph: C Sanders, QAGOMA

Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori and Timothy Cook are linked by their bold, gestural marks; the reach of these artists’ arms is on full display across their canvases. Cook’s swinging, looping lines of the moon and yam in Kulama 2012 and Kulama 2012 echo the circles of the ceremonial dancers around the firepit during initiation events. The cycles of the moon and bodies in ceremony are also referenced in Clare Milledge’s Sruth 2021, which draws upon the artist’s Irish heritage; while Mikala Dwyer’s cloaks and masks that hang on the gallery walls in artwork imply an imminent, or recent, ritual event.

Major life events are elegantly referred to in artworks by Yolngu artists Mr Wanambi and Dhuwarrwarr Marika. Larrakitj (memorial poles) are normally highly decorated, but Mr Wanambi leaves his in their natural form, painting them only white — a colour associated with sorry business. The circular pattern in Dhuwarrwarr Marika’s painting Milngurr 2018 is a reference to the fontanelle, signalling new life, and the piercing of the land to create a waterhole. In this work, the body and the land are inseparable.

‘Living Patterns’ also includes artists whose artworks point to their own migrant culture. For instance, to keep an aesthetic tradition alive, Salote Tawale reimagines masi (barkcloth), making her work out of materials easily accessible at a hardware store. Constanze Zikos interrogates the idea of ‘authentic’ culture by using faux wood and mass-produced materials. In U Robe 2021, Zikos looks at articulations of the ancient arts of Greece are articulated in the contemporary suburbs of Australia.

A view of Salote Tawale’s You/me #1, Us and You/me #2 2019 installed for ‘Living Patterns’, QAG, September 2023 / Courtesy: Artbank, Sydney / © Salote Tawale / Photograph: C Sanders, QAGOMA

Vivenne Binns and Hossein Valamanesh are each inspired by the use of Islamic geometry in architecture (in modern Spain and Iran, respectively) and celebrate how decorative design infuses ideas of abstraction into the everyday. Paul Bai and Lindy Lee each reference Chinese art history in different ways. Bai’s work considers the importance of negative space in the traditions of Chinese calligraphy and painting, placing just two dots on the gallery wall to draw our attention to the blank space. Lee’s meditative approach is influenced by Buddhist practices; here, in her ‘weather paintings’, she applies ink to the paper before allowing the wind and the rain to move it across the surface — letting the final artwork embody, rather than represent, the forces of nature.

If you look around ‘Living Patterns’, you will see jewel-like works from Lauren Burrow’s ‘Slow plosion’ series 2022. The shapes of its sculptures are taken from sections of Birrarung (the Yarra River in Victoria). Burrow’s use of broken glass references the industrial blasting of the river, while also creating a dappled reflection of light, akin to ripples on the water. Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori’s Dibirdibi Country 2012 is an ode to her late husband and his place — a freshwater well created by and named for Dibirdibi (the Rock Cod Ancestor). By energetically working white paint into the still-wet layers of dark blue, the artist has captured the creative and destructive forces that brought the well into existence. Simon Wilson Pitjara’s paintings look at the recitation of songlines and the Country that they relate to, using a television screen as a painting surface. The artist’s songlines overcome the violence implied by the broken screen and stalwartly continue to broadcast their own existence. Looking at these works, it is hard to ignore that the ubiquity of screens in our lives relies on the copious mining of raw materials.

Lauren Burrow introduces works from ‘Slow Plosion’ 2022 on a ‘Living Patterns’ tour, with d harding’s Moonda and The Shame Fella 2018 visible in the foreground, QAG, September 2023 / © The artists / Photograph: C Sanders, QAGOMA

Many of these artists in ‘Living Patterns’ explore ideas of transmission — how images and information are broken down and reformed. Scott Redford’s Reinhardt Dammn: Things the mind already knows 2010 takes as its inspiration a symbol once shown on television at the end of each evening’s broadcast. The ‘test pattern’ was once the most common abstract image that anyone would see — an icon, perhaps, for those rejecting the routines imposed by the standard nine-to-five workday. Now, in a second layer of abstraction, most young people may not recognise it at all.

In addition to Daniel Boyd’s Untitled (HNDFWMIAFN) 2017 mentioned earlier, a group of works within ‘Living Patterns’ deals with the obfuscation of labour. Emily Floyd’s immersive ‘public library’, entitled Labour Garden 2015, creates a playful space for collective contemplation and discussion of essays that wrestle with the complexity of contemporary working conditions. Different illustrations of labour — from the symbol of the striking tram driver to washing-up chores and the well-dressed bourgeoise — feature in Helen Johnson's Women's work (1912) 2017. The images are so densely layered that it is hard to make out the imagery — a visual metaphor for the entwinement of historical issues.

An installation view of ‘Living Patterns’, featuring Helen Johnson’s Women’s work (1912) 2017 in the foreground, QAG, September 2023 / © The artists / Photograph: C Sanders, QAGOMA

Artistic labour is on show in many of these works of art. Each stitch among the thousands that make up Teelah George’s A Pearl Necklace 2022 becomes a marker of the artist’s hand, as well as the passing of time. Similarly, Margaret Rarru’s Dhomala (Macassan canoe) sail 2019–20 is testament to the meticulous skill of the artist — not only to weave, but also to harvest, dry and dye the pandanus too. In Buyku 2019, Djirrirra Wunungmurra incised the bark before adding an intricate net of painted diagonal grids, creating a dazzling surface. In Hilarie Mais’s Lace ghost 2018, the shifting washes of paint and crude application of plaster over the joins in its web of wood, draw attention to the method of production. In addition to their industrious approaches, both Wunungmurra and Mais are sensitive to the contributions of absence and negative space to the visual power of an artwork.

‘Living Patterns’ invites slow looking — that is, moving away from images manufactured to be understood within a half-second scroll on social media. Christian Capurro’s ‘enclasticine’ series 2017–21 reflects on image-editing software, which enhances and otherwise tweaks so many of the pictures we consume via screen. Here, Capurro has applied an algorithm that ‘cleans’ images; while the result contains multiple mutations, something of the original image persists.

Christian Capurro introduces works from his ‘enclasticine’ series 2017–21 on a ‘Living Patterns’ tour, QAG, September 2023 / Courtesy: The artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane / © Christian Capurro / Photograph: C Sanders, QAGOMA

Other exhibited works are also informed by scientific ideas draw on histories of Op [optical] art and minimalism. Taree Mackenzie’s Pepper’s ghost, wind turners, blue and yellow 2018 and Jonny Niesche’s ‘Schein blossom’ series of interference-pattern prints play on perception — how light, colour and movement influence what your eye sees. Meanwhile, the reduced palettes of Teelah George, Carbiene McDonald Tjangala and Gemma Smith’s restrained palettes reward close looking; their subtle shifts in colour draw the viewer’s eye around each composition. At first, Smith’s Rotate 2019 might look like a blank canvas, but it becomes charged and dynamic over time.

Many of these works, if you let them, can heighten your attention to nuance. In moving around ‘Living Patterns’, you may find these artists and their works in unexpected conversation, their themes and histories overlapping in the liminal space abstraction allows. Take your time.

Ellie Buttrose is Curator, Contemporary Australian Art, QAGOMA.