Isaac Walter Jenner: Curating a feeling for light

By Michael Hawker

Artlines | 3-2023 | September 2023

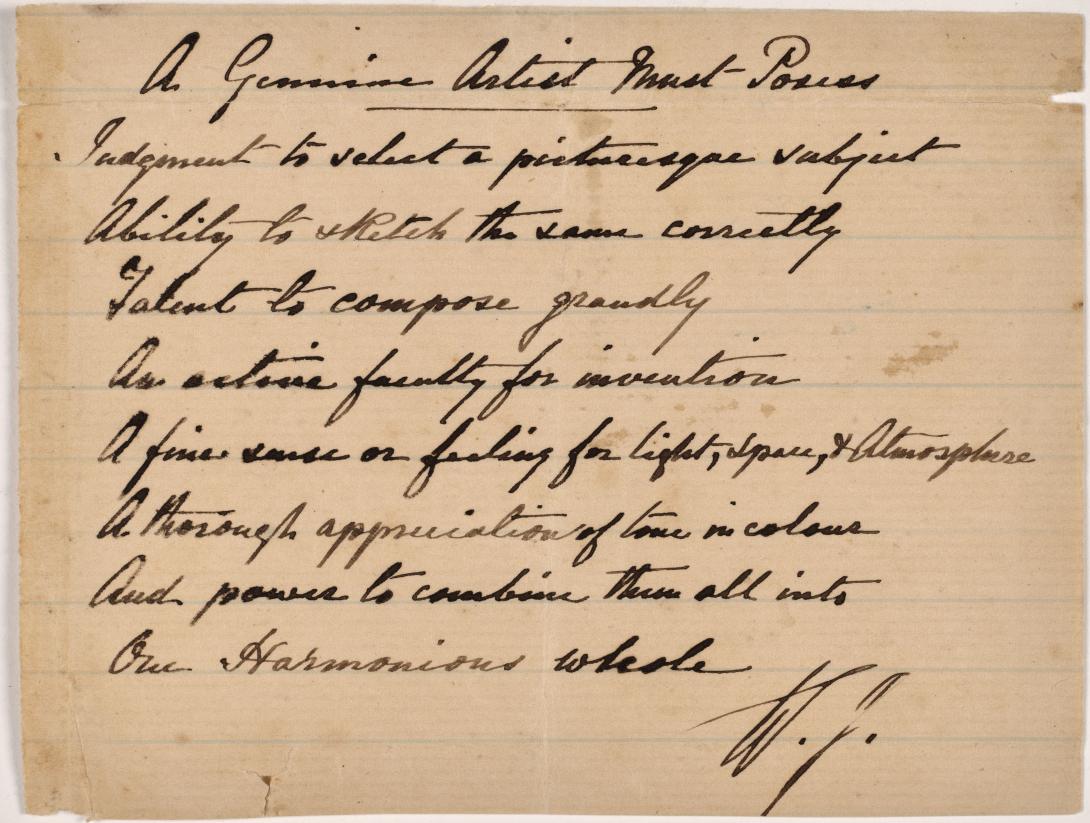

A genuine artist must possess judgement to select a picturesque subject and ability to sketch the same correctly; talent to compose grandly; an active faculty for invention; a fine sense of feeling for light, space and atmosphere; a thorough appreciation of tone in colour; and power to combine them all into one harmonious whole.

— Isaac Walter Jenner

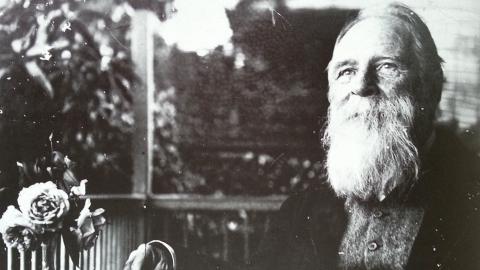

On leaving the Royal Navy in 1865 after eleven years’ service, Isaac Walter Jenner first established himself as a professional artist in Brighton, England. Just shy of two decades later, at the age of 47, he migrated to Australia with his wife and their seven children, arriving in Brisbane on 19 September 1883. Jenner quickly established himself as a leading artist in the city, working diligently to raise the public’s awareness of art by helping to found the Queensland Art Society and organising exhibitions. His activities also contributed to the establishment of the Queensland National Art Gallery — now known as the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) — back in 1895. As early as 1884, Jenner was campaigning in the local newspapers for the founding of a public art gallery. He wrote to the Brisbane Telegraph: ‘… a building is needed in some part of Brisbane … for pictures … sculpture, a good library, and museum of natural history’.1 Jenner brought a seriousness and determined professionalism to his new home, focusing discussions among his peers and acting as a role model to other local artists. He encouraged the teaching of art and worked with young artists both in the school system and as a private teacher.

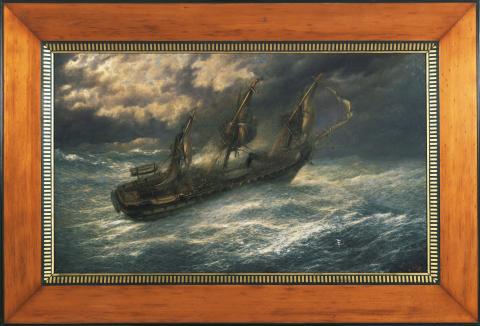

Isaac Walter Jenner / England/Australia 1836–1902 / The 'Retribution' at Balaclava during the Crimean War 1895 / Oil on canvas / Purchased 1975 / Collection: QAGOMA / Photograph: C Callistemon, QAGOMA

Jenner’s early years in the Navy — where he was classed as a seaman and tasked with ship maintenance, which involved painted finishes, decorative work and signwriting — ‘intimately acquainted [him] with the details of construction and rigging, knowledge that would be of great value in his later career as a marine painter’.2 The QAG exhibition has a fine display of these early works, which concentrate on sea, sky and ships. In these paintings, he creates an atmosphere drawing on acute observation of light and shadow, the use of colour, and the sailor’s keen eye for weather effects. Wild storms, gale force winds and battered ships are evoked in works like The ‘Retribution’ at Balaclava during the Crimean War 1895, to more tranquil scenes with clouds of golden light, as seen in HMS Victory at Portsmouth c.1881. Both were ships he had served on during his naval career.

At the age of 29, having left the Navy, Jenner’s establishment as a respected professional artist in Brighton was an amazing feat, considering his background and lack of formal artistic training. He exhibited at the Royal Academies in London and Edinburgh, at Brighton’s Royal Pavilion Gallery, at Lewes, Bournemouth, and the Crystal Palace, London. Despite sales and exhibitions, Jenner’s position in fashionable nineteenth-century Brighton was likely to have been insecure; although there is no concrete evidence for his motivation to migrate, tales of wealth and success must have been a factor — after all, he was not an officer-turned-artist, just a sailor.

The QAGOMA Research Library holds ephemera like this undated handwritten note by Isaac Walter Jenner, titled ‘A Genuine Artist Must Possess’ / Collection: QAGOMA Research Library / Photograph: J Ruckli, QAGOMA

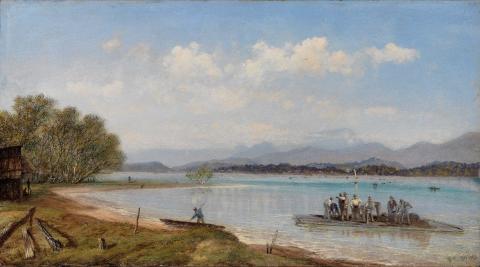

Stylistically, Jenner was an artist caught between two worlds. His heart and inspiration lay with his old world of romantic English landscapes filled with the soft light of dawns and sunsets, set against rugged coastlines, ships and the sea. While the prevailing contemporary trend was to a truer interpretation of the Australian light, Jenner’s art was imbued with a sublime romantic spirit. While he painted Queensland scenery, he also continued to paint English scenes, from memory, all his life; consequently, his work was often perceived as ‘European’, which further reduced its awareness and appreciation after his death. At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, there was a new sense of nationalism, with painters depicting peculiarly Australian qualities of life, light and landscape, and turning away from the sublime, picturesque style exemplified in the landscapes of such artists as Eugene von Guérard and Conrad Martins. Jenner’s atmospheric paintings owe more to Dutch and British marine painting, JMW Turner, and earlier Australian colonial painters than they do the works of Arthur Streeton, Tom Roberts and Frederick McCubbin — his contemporaries in Australia.

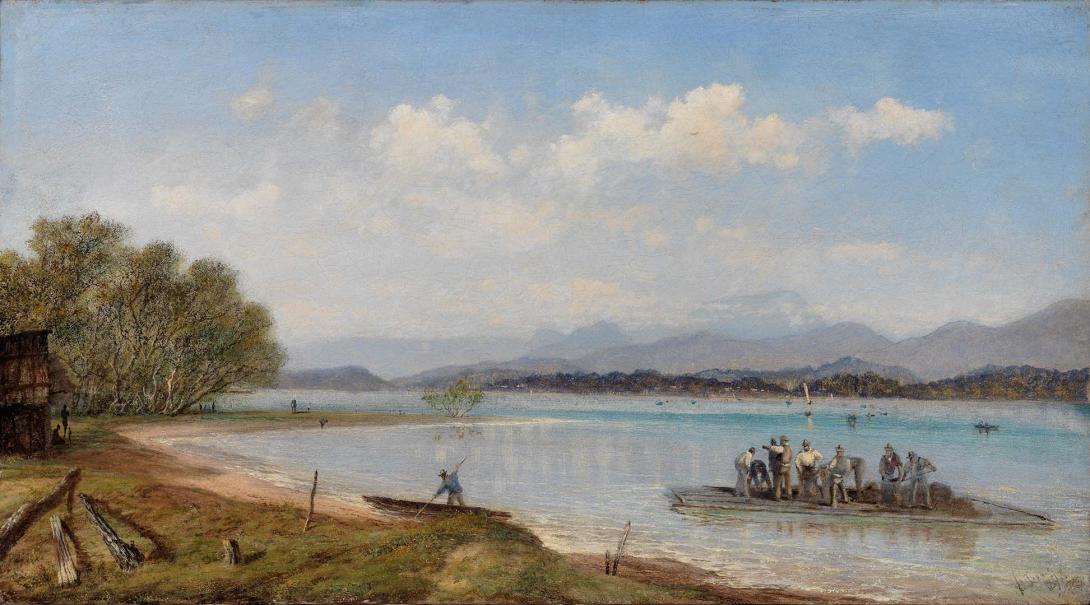

Beyond atmospheric effects, Jenner’s art characteristically displayed other more subtle established conventions to convey the sublime: frail, seemingly insignificant human figures contrasted with the forces of nature, exaggerating their power and size; the relentless motion of the sea; dark menacing rocks and towering cliff faces; the clouds dramatically lit by the light of the sun, setting or rising. These qualities found expression in his paintings of Queensland subjects. Queensland natives, the Currigee Oyster Company's Station, Stradbroke Island, Moreton Bay 1897, for instance, reveals Jenner’s application of English picturesque precepts to the Queensland coastline. The setting is tranquil, most probably an early morning scene, with the clouds still suggesting the late flush of sunrise. A group of men working from a raft provides the foreground ‘interest’ of the composition, while the middle and far distances are punctuated by groups of figures and by boats on the bay. These figures are typical of the picturesque ideal, evoking a sense of human beings at ease in their surroundings. Importantly, to the left of the painting, there is an Aboriginal family group, and in the left middle ground, several more individuals can be seen. Apart from the Swedish-born artists and brothers Oscar and Edward Friström, few colonial painters in Brisbane featured Indigenous Australians.3

Despite his great contributions as artist and advocate, Jenner has never been fully appreciated. He remains little known outside of Queensland, partly because he did not sell his work in the larger colonial centres of Sydney and Melbourne — preferring to send many of his works to England for sale. With this exhibition, we hope to bring his considerable achievements to light, for present and future generations.

Michael Hawker is former Curator, Australian Art at QAGOMA.

Endnotes

- Isaac Walter Jenner, ‘The proposed art gallery’, Letters to the Editor, Daily Telegraph, 8 December 1884, p.5.

- Gavin Fry and Bronwyn Mahoney, Isaac Walter Jenner, Beagle Press, Sydney, 1994, p.16.

- QAGOMA Collection essay on Jenner’s Queensland natives, the Currigee Oyster Company's Station, Stradbroke Island, Moreton Bay 1897, based on notes prepared by Chris Saines and Bettina MacAulay.

Digital story context and navigation

ISAAC WALTER JENNERExplore the story