The land has everything it needs. But it couldn’t speak. It couldn’t express itself. Tell its identity. And so it grew a tongue. That is the Yolngu. That is me. We are the tongue of the land. Grown by the land so it can sing who it is. We exist so we can paint the land.

— Madarrpa artist Djambawa Marawili1

An evolution of bark painting

Artists across Australia’s northern coastline, from the Kimberley in Western Australia to far eastern Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory, have used crushed earth pigments from their lands on sheets of eucalyptus bark to paint powerful, mysterious images of deep cultural significance, reiterating their spiritual connection with specific tracts of country. A selection of these works, contemporary and historic, is shown in ‘Transitions’, offering a unique experience of the breadth and depth of one of the world’s richest continuing and most ancient artistic expressions.

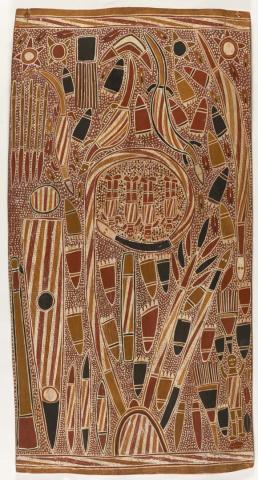

In ‘Transitions’, elemental early bark paintings are shown alongside more refined contemporary barks and painted memorial poles to chart the evolution of Australian Aboriginal bark painting over eight decades. Across the exhibition, a ripple of change in content and style can be discerned in works grouped to reflect clan and country affiliations from west to east, tracking complex, interconnected narratives and sites that map the vast northern Australian landscape and its unparalleled linguistic and cultural diversity.

Aboriginal painting and sculpture have given voice to poetic stories linked to the creation of the landscape. In annual rituals, people paint their bodies with earth pigments and perform song cycles and dances recalling ancestral creative acts at specific sites. Everything and everywhere is imbued with meaning.

Works installed for ‘Transitions’, including (far left) James Iyuna’s Rarrk (Clan design) burial pole 2007 / © James Iyuna/Copyright Agency; and Gulumbu Yunupingu’s Garak, The Universe 2004 and Gan'yu (Stars) 2007 / © Gulumbu Yunupingu, courtesy of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala, GOMA, August 2022 / Photograph: M Campbell, QAGOMA

Elemental materials

The bark used in northern coastal Australia for paintings, canoes and bush shelters is invariably from the versatile stringybark (Eucalyptus tetrodonta). After seasonal rains have caused the sap to rise, large sheets of bark — easily prised off the tree and cleansed by fire, then flattened, seasoned and smoothed — offer an inviting painting surface. Artists are often inspired by the unique qualities of a fresh sheet of bark, which may even suggest the subject of the painting. A work may also be guided by the natural pigments used, which retain spiritual connections with their source. The colours used in bark painting (commonly derived from red and yellow ochres, white pipe clay and black charcoal saved from cooking fires) have been described as standing for black skin, white bones, red blood, yellow body fat and the sun.

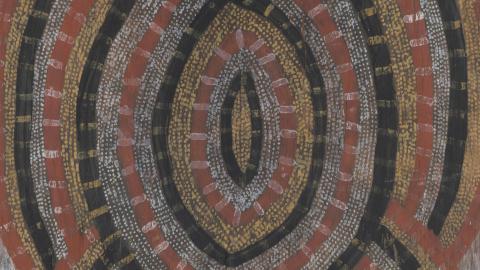

Within these constraints, colour choices can be very personal. Celebrated Yirrkala artist Gulumbu Yunupingu (1943–2012) often carried a ‘rock bag’ with her, holding three or four reds and subtly different whites and yellows. She mixed black and white to make grey, black and yellow to make green and red and white to make pink — and even collected a special soft pale yellow at Darwin’s East Point, being certain to acknowledge the Larrakia traditional landowners for their permission. Pigment and place have multi-layered connections — for example, a prized pure white found in western Arnhem Land is believed to be the excrement of the Rainbow Serpent and must be mined in accordance with strict protocols.

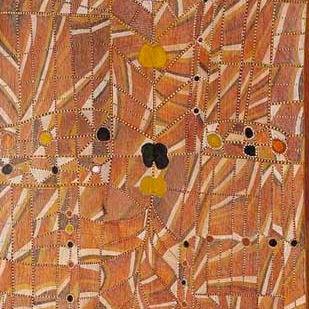

In preparation for painting in recent times, raw pigments are finely ground on a flat stone mixed with wood-working glue and water.2 The prepared surface is given an overall coating of pigment. Depending on the subject, after an initial dynamic drawing the image is colour-blocked and infilled precisely with rarrk or dotted patterns, applied with fine brushes made from plant fibres or human hair. (‘Rarrk’ is an intricate system of cross-hatched patterns in clan designs, carrying ancestral power.) Some artists are even bound to paint cross-hatching in a prescribed colour sequence according to their moiety and clan affiliations. Artists mostly work in-the-round with the bark on the ground — there is no quick and easy way to make a bark painting in the traditional way.

While the bark and natural pigments of their predecessors are still the materials of choice for many artists, some have taken new approaches to accommodate the specific nature of the raw material. As barks commonly buckle, bend, warp and twist, adapting to awkward surface variations and exploiting undulations, textures, knots and irregular edges can add interest to a work.

Imagery and patterning on barks and poles originate in body paintings. In eastern Arnhem Land, for example, the miny’tji (sacred clan signatures) painted onto a boy’s body during initiation into manhood are unique to his clan group and inextricably linked to his identity through life — and after death, painted on ritual sculptures, coffins or hollow log memorial poles. Customary laws embodied in the designs determine land custodianship, where people can walk or hunt, who they are related to and how those relationships are lived.

The birth of the modern era of Aboriginal art may be traced back to 1912, when anthropologist Walter Baldwin Spencer first purchased and commissioned paintings by artists at Gunbalanya (Oenpelli) in Western Arnhem Land. Over the next decade, Spencer worked with his local collaborator, buffalo hunter Paddy Cahill, to acquire a significant collection (now held by Museum Victoria).3

QAGOMA’s Collection holds some of the earliest bark paintings to enter a state art institution: works collected in 1948 during the comprehensive American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land led by Charles Pearcy Mountford (1890–1976). Mountford was a skilful amateur ethnographer who, unusually for the time, appreciated bark paintings as art rather than artefact. Gallery directors from each of the six state art galleries (rather than museums) met in Brisbane in August 1956 to select works from 500 Arnhem Land paintings on bark and card resulting from the expedition, with 144 total works (24 per institution) distributed across Australia. Though the paintings weren’t readily accepted as ‘fine art’ by most Australian art professionals — and tended to languish in storage rooms for some years — the expedition was widely publicised, bringing the Aboriginal cultures of Arnhem Land to international attention.

An early champion of Aboriginal bark painting was Czech artist and amateur anthropologist Karel Kupka. In author and journalist Nicholas Rothwell’s essay ‘The Collector’ in the October 2007 edition of The Monthly, writing on Kupka, Rothwell describes his admiration for the influential French artist Andre Breton: ‘. . . the master-thinker of the surrealists and a man keenly receptive to the appeal of tribal art’. When living in Paris, Kupka would often ‘make visits to Breton’s studio on the Rue Fontaine, where works from Africa and Oceania were hung alongside paintings from the European surrealist circle’.4 He began to visit Parisian museum collections of tribal art and was inspired to come to Australia to discover the unique qualities of Aboriginal art and culture.

In Melbourne, Kupka met the photographer Axel Poignant (1906–1986), who’d had a recent intense experience photographing people at Nagalarramba (on the western bank of the Liverpool River in central Arnhem Land), and painter Carl Plate (1909–77), a leading figure in Australia’s post-war modern art movement. They were able to point him to the few accessible public displays of Aboriginal art and, in the northern Australian dry season of 1956, Kupka flew to Milingimbi Island (Yurrwi) off the coast of central Arnhem Land to discover the source of the paintings that so intrigued him.

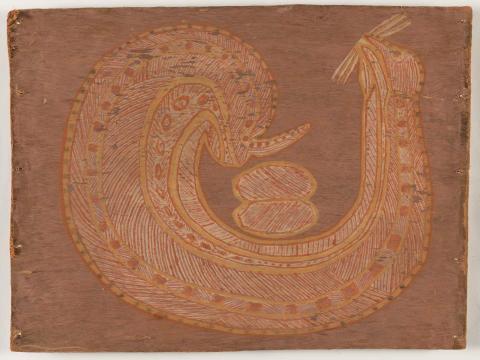

Kupka spent much of his time on Yurrwi with two senior artists, Djawa and Dawidi, and learnt much from them. Djawa’s paintings were strongly influenced by his involvement in secret-sacred ceremonial rituals and Liyagalawumirr artist Dawidi’s were rich with signs and symbols — ‘a style ideally suited for decoding by the Western eye’, as Rothwell puts it.5 Wagilag sisters c. late 1960s by Dawidi, included in ‘Transitions’, exemplifies this quality.

On his return from Arnhem Land, an exhibition showing some of the works Kupka had collected was held at the East Sydney Technical College (now the National Art School) and opened by AP Elkin, ‘long-standing professor of anthropology at the University of Sydney’ and author of Aboriginal Men of High Degree, the ‘sympathetic account of Aboriginal witchdoctors and magic men . . . that preserves his name today’.6

While in Arnhem Land, Kupka had studiously sketched and documented many bark paintings in detail, with the idea of educating and exciting European museum curators. He communicated his passion for Aboriginal art so successfully to Professor Alfred Buhler (the director of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Basel) that, in the relationship of trust that developed between the two men, Kupka was commissioned to source a collection of Aboriginal works for the museum. Ultimately, Karel Kupka’s visits to remote Australia would spark a new chapter in Western appreciation of Aboriginal cultures.

In gratitude for his encouragement, Kupka presented Breton with a large bark by Paddy Compass Namatbara depicting two Maam figures and, for several decades, these spirit-beings hung alongside Hopi masks and masterworks of high modernism on the walls of Breton’s Paris studio. (Another of Namatbara’s works, Untitled (spirit figures) c.1960, is included in this exhibition.) Interest spread and art collectors and audiences gradually became more accepting of Aboriginal graphic traditions as fine art.

Another early enthusiast for the aesthetic qualities of northern Australian Aboriginal art was Australian artist and arts administrator Tony Tuckson who, through his roles from 1950 to 1973 at the Art Gallery of New South Wales as an attendant and as Deputy Director, was the first in a major Australian art gallery to seriously acquire and commission Aboriginal works for a public art institution. At that time, though there was still debate about whether bark paintings had a place in a fine art museum, Tuckson was convinced that the beauty and power of Aboriginal art would move and enlighten audiences through direct experience with the works.

In the late 1950s, Tuckson travelled with his wife Margaret, benefactor Dr Stuart Scougall and Aboriginal dealer Mrs Dorothy Bennett to the Northern Territory and into Yirrkala in north-eastern Arnhem Land, where he commissioned a group of bark paintings. The resulting invaluable collection of magnificent barks from Yirrkala remains at the heart of the AGNSW collection of Aboriginal art.

Having previously studied art at the East Sydney Technical College, Tuckson privately conducted his own art practice; his first solo exhibition at Watters Gallery in 1972 (and a further exhibition in 1973) cemented his reputation as a leading Australian abstract expressionist. His emotional response to the aesthetic qualities of Tiwi Islands and Yolngu art and his brave ‘controversial’ displays at the Gallery — for example, his grouping of Tiwi Islands (Melville) pukumani poles as a sculptural installation in 1960 — were influential in popularising Aboriginal art in Australia. Originally consecrated with sacred designs and left to weather in the community, pukumani poles and hollow log burial poles from Arnhem Land (used customarily for the interment of prepared human bones) are now often virtuoso pieces by widely recognised artists, shown singly or in large groups in contemporary art installations.

Other influential Australian visitors to Arnhem Land included Donald Thomson, Ronald and Catherine Berndt, Jim Davidson, Helen Groger-Wurm and Americans Edward L Ruhe, Louis A Allen and Gerome Gould.

As the Aboriginal bark art movement gathered momentum in the 1980s, discerning collectors commissioned or selected paintings on the basis of their visual appeal, with a preference for large-scale works, innovative styles and subjects, finer line work, balanced composition, strong graphic elements and a painterly finish. The market evolved through the supply channels of missionaries and anthropologists in the field, visiting enthusiasts, community art and cultural institutions, and art dealers in the cities to accommodate the increasing interest. As Aboriginal artists steered production toward demand — adding polyvinyl acetate fixative to the earth pigments for longevity, and refining painting techniques — bark painting was subtly modified to more closely resemble modern art. In 1981, Hogarth Galleries in Sydney held a solo show of classic barks by John Bulunbulun (1946–2010) from Maningrida in central Arnhem Land — the fine works were a revelation to many viewers. Aboriginal bark art thrived and is now represented in all major Australian art institutions and in private collections.

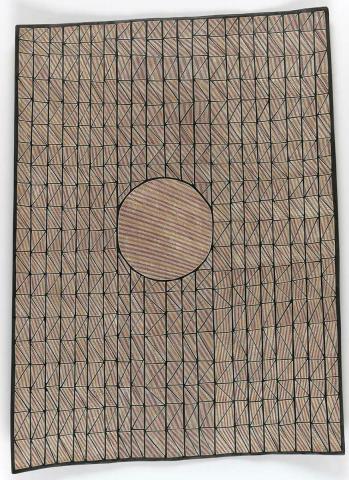

Ngaymil 2015

- GANAMBARR, Gunybi - Creator

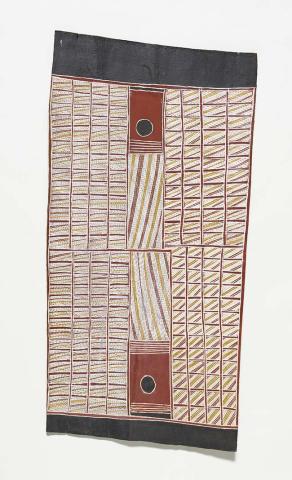

Djirrit 2021

- GANAMBARR, Gunybi - Creator

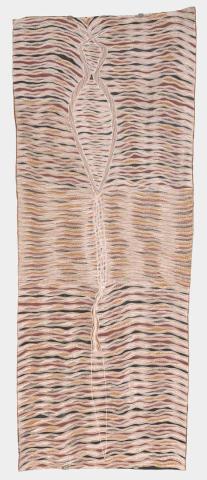

Milngurr 2007

- MARIKA, Dhuwarrwarr - Creator

A figurative invisibility

In 2003, at Buku Larrnggay Mulka Centre in Yirrkala, Wanyubi Marika described a geometric ‘style’ of painting developing in the school of local artists at Yilpara (Baniyala) as ‘Buwayak’ (meaning ‘Invisibility’) — the process in which the figurative cover had begun to disappear from view.7 Now, stylish, innovative displays developed collaboratively with artists and communities often feature the abstract clan designs, still deeply connected to ceremonies and creation narratives.

More recently, innovative artists from Yirrkala have begun to shape large sheets of bark, glue bark shavings on to create a shallow relief texture, incise patterns into bark surfaces and paint contemporary narratives. And even more radically, Gunybi Ganambarr began engraving sheets of disused water tank metal, repurposing local road signs and discarded building materials and even incising slabs of dense, black, industrial-grade conveyor-belt rubber. Ganambarr was the first to use these materials creatively, re-examining the age-old tenets set by his elders to ‘use only materials from the environment’ to include working with manmade materials abandoned on his land.

Whether bark painting, or the whole spectrum of work we know as contemporary art, Aboriginal art makes compelling statements on the power and beauty of Aboriginal culture and remains one of the few self-directed financial avenues available to Australia’s First Nations artists.

The QAGOMA Collection

The Gallery’s collection of Australian bark paintings includes works dating back to the 1940s, with works acquired during the 1948 American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land — led by Charles Mountford — gifted to the Gallery in 1956. In 2003 the Gallery acquired at auction the much-loved major works Balirlira and the Macassans c.1958 by Larrtjanga Ganambarr and Yalangbara c.1960 by Mawalan Marika (with seven other artists). From then, in a focused drive up to the present, a significant group of bark paintings and an important group of hollow log memorial poles have entered the Collection, representing a period of dramatic transition in individual painting styles and subjects. The evolving high levels of refinement and experimentation are particularly evident in works by John Mawurndjul, James Iyuna, John Bulunbulun and Michael Gadjawarla of Maningrida; Micky Durrng of Milingimbi and Nawurapu Wunungmurra, Gulumbu Yunupingu, Djambawa Marawili, Gunybi Ganambarr and Mr W Wanambi from the Yirrkala region — deservedly earning the artists national and international recognition.

In 2020, the Gallery’s existing collection was significantly enhanced by the generous donation of 66 barks assembled over many decades by collector Robert Bleakley, including rare early works from the Kimberley in Western Australia and, in the Northern Territory, from Wadeye, Tiwi Islands, Groote Eylandt and western, central and eastern Arnhem Land — considerably broadening the scope for representing the bark painting genre.

Dhuwarrwarr Marika received a classic art education from her father Mawalan Marika (1908–67) at an early age. Though they share similarities in style and content, Dhuwarrwarr developed her own distinctive, minimalist practice using bold, stylised imagery. Still painting, she has seven works in the Collection: on bark, on a wooden memorial pole, a discarded wooden board and even in enamel on an aluminium panel. Other dedicated women artists who have emerged more recently are now widely celebrated in major exhibitions, with their work much in demand.

Included in ‘Transitions’ are Djirrirra Wunungmurra’s barks finely incised with abstract patterns and Gulumbu Yunupingu’s exquisite star maps. In a weaving style drawing on her Kunwinjku family’s painting aesthetic, Anniebell Marrngamarrnga’s slender woven sculpture of Yawkyawk (Female water spirit spirit) pregnant with twins 2007 recalls their presence in freshwater sites in the western Arnhem Land escarpment, where they sit on boulders to languidly dry their long tresses (algae strands).

Anniebell Marrngamarrnga’s Yawkyawk (Female water spirit) pregnant with twins 2007, installed for ‘Transitions’, GOMA, February 2023 / © Anniebell Marrngamarrnga/Copyright Agency / Photograph: N Harth, QAGOMA

Collection works from Arnhem Land

The artistic communities of western, central and eastern Arnhem Land have been the most prolific and prominent in traditional bark painting and, in recent years, for introducing new materials and content into their practice.

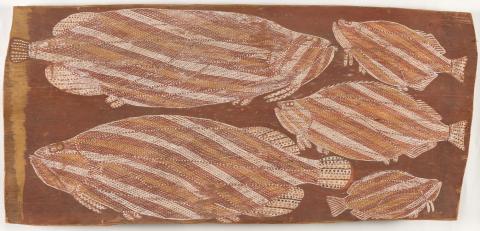

Two crocodiles 1958

- YIRRWALA - Creator

Western-Central Arnhem Land

Eastern Kunwinjku artists live in lands that straddle the boundary between western and central Arnhem Land and their art is often a fusion of the two cultural and artistic traditions. Living amongst caves and open rock art ‘galleries’ is a constant source of inspiration for them, and they even attribute their knowledge and skills to the guidance of the mimih spirits depicted there. The dynamic mimih figures may still be the most significant influence for contemporary painters of the region.

As a viable market grew, Eastern Kunwinjku artists refined their techniques, but the iconic figures of ancestral spirits and totemic animals remained central to their art, peaking in the late 1980s when rock art was the all-consuming inspiration for eastern Kunwinjku painters. Bold images on barks over two metres high were never made with a conservative market in mind, but rather to confront the viewer warning of the potency and dangers of the escarpment country.

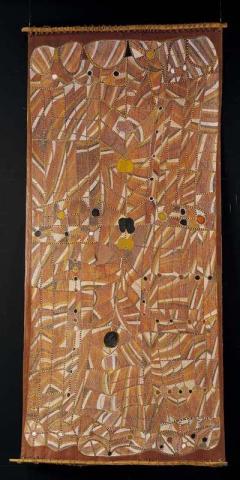

Subsequent to this figurative period, these artists increasingly began using rarrk cross-hatching in layers of fine lines drawn onto the bark surface after the original outline is laid down and colours infilled — the lines of rarrk being produced in a rhythmic action by dipping the long-haired brush into the wet pigment and stroking it away from the body. Segmented areas of optical patterning (that could be read almost as abstract paintings within the larger work) became signature devices for individual artists; appreciative national and international audiences gave impetus to this movement for its seeming convergence with Western minimalist aesthetics.

Two of the most successful of this school are James Iyuna (1959–2016) and his brother John Mawarndjul (b.1952) — whom TIME journalist Michael Fitzgerald described as ‘the Michelangelo of rarrk’.9 Mawurndjul gained international fame for his work when commissioned in 2006 to paint for the Musee du Quai Branly, Paris and even appeared on the cover of TIME magazine in May of that year.10 The title for his solo exhibition held at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 2018, ‘John Mawurndjul: I am the old and the new’, reflects his self-proclaimed role as a forward-thinking bark painter. Iyuna’s Namorrgon (lightning) in ‘Transitions’ is an energy-releasing spirit to be feared and respected and Mawurndjul’s Mardayin and wongkurr (Sacred objects and dilly bags) depicts sacred objects and woven baskets — their power obscured by sacred rarrk.

Central Arnhem Land

Central Arnhem Land country is largely savannah woodlands, fresh-water swamps and major rivers, and the islands and coastline of the Arafura Sea. These artists depict complex narratives describing the creation of specific tracts of land and the identities and connections over vast distances of the people who live there. Many images also articulate the responsibilities and means for keeping the environment in balance and maintaining social harmony.

Bark paintings from this region also reflect important influential histories — from the interaction over hundreds of years with Macassan fisher-traders (visiting seasonally from present-day Indonesia), to the establishment of the first Christian missions; the influence of World War II; the arrival of serious researchers and the interest of collectors, some of whom saw great potential for the inclusion of Arnhem Land art in Australian and international collections and for exhibition on the world stage. Within these works lies the genesis of the central/eastern Arnhem Land art movement, illustrating the varied painting styles of diverse multi-lingual groups and artist families, whose early works connect directly, through family lineages, with the more modern barks in the QAGOMA Collection.

Artists from the central region relate to Maningrida Settlement and Maningrida Arts and Culture, set up in 1973 to support and encourage artists to paint for the growing market. As in other community art centres, it provides logistical assistance to artists; records and documents works; and markets them through general sales and exhibitions, ensuring that artists are well-represented and properly remunerated.

Mick Naromi typically painted in an abstract style where imagery was subsumed into a mosaic of rarrk patterning divided by dotted lines. Central to his painting Wandurk: Spirit figure from Gurrgoni Country 1980 is the spirit being associated with a tract of Gurrgoni stony land close to the road leading out of Maningrida. Passers-by are obliged to show respect by calling out to acknowledge Wandurrk and to ask for permission to be on the land and to ensure a safe journey.

Bark paintings from this region also reflect important influential histories — from the interaction over hundreds of years with Macassan fisher-traders (visiting seasonally from present-day Indonesia), to the establishment of the first Christian missions; the influence of World War II; the arrival of serious researchers and the interest of collectors, some of whom saw great potential for the inclusion of Arnhem Land art in Australian and international collections and for exhibition on the world stage. Within these works lies the genesis of the central/eastern Arnhem Land art movement, illustrating the varied painting styles of diverse multi-lingual groups and artist families, whose early works connect directly, through family lineages, with the more modern barks in the QAGOMA Collection.

Artists from the central region relate to Maningrida Settlement and Maningrida Arts and Culture, set up in 1973 to support and encourage artists to paint for the growing market. As in other community art centres, it provides logistical assistance to artists; records and documents works; and markets them through general sales and exhibitions, ensuring that artists are well-represented and properly remunerated.

Mick Naromi typically painted in an abstract style where imagery was subsumed into a mosaic of rarrk patterning divided by dotted lines. Central to his painting Wandurk: Spirit figure from Gurrgoni Country 1980 is the spirit being associated with a tract of Gurrgoni stony land close to the road leading out of Maningrida. Passers-by are obliged to show respect by calling out to acknowledge Wandurrk and to ask for permission to be on the land and to ensure a safe journey.

For a period in the late 1980s, Gochan Jiny-jirra community, set in rich, well-watered lands on the Cadell River, was a creative hub where artists — painting in their simple outdoor ‘studios’ — encouraged each other to achieve great artistic heights, with successful joint exhibitions of their work to critical acclaim. Terry Wilson Ngamandara developed a unique sparse, finely drawn style, mixing black and yellow pigments to make a signature green colour, as in Waterhole at Barlparnarra 2007.

Artists included in ‘Transitions’ are from various central Arnhem Land language groups.

Eastern Arnhem Land

On certain days, Yirrkala and the surrounding lands and waters of the Arafura Sea epitomise our perception of a tropical ideal. A vast blue sky over warm clear waters abundant with marine life, open savannah woodlands, jungles and swamps rich in bush food and a dazzling night sky. Yolngu artists of the eastern Arnhem Land region know their country well and have long valued its beauty and their Ancestral links with its creation. When necessary, they have painted important barks to create comprehensive spiritual and political records of their rights to clan lands.

Mawalan Marika (1908–67), the revered leader of the Rirratjingu people of north-eastern Arnhem Land and father of a dynasty of talented artists, began painting barks for sale through the mission as early as 1935. He attracted many well-known Australian and international researchers and collectors to Yirrkala eager to meet the artist. He and his brother Mathaman Marika (c.1916–70), sensing the enormous changes taking place that would permanently alter Yolngu culture and lifestyle in their lifetime, painted important Rirratjingu creation stories on bark depicting the interconnectedness of north-east Arnhem Land clans.

In 2003, the Gallery acquired the bark painting Yalangbara c.1960 by Mawalan 1 Marika and seven other artists at a Sotheby’s auction in Melbourne. This precious work was in pristine condition, having been carefully stored since the 1960s in the home of Reverend Rankine, Superintendent of the Methodist mission at Yirrkala (1958–62). The deep knowledge and passion for truth and justice that the current artists of north-eastern Arnhem Land inherited from their forbears are the catalysts that commit them to ever more creative expressions in their art.

In 1962–63 the two monumental ‘Yirrkala Church Panel’ works were painted to explain Yolngu relationship to and declare ownership of their clan lands.11 They predated the Yirrkala bark petition of 1963, presented to the Australian Parliament in an attempt to stop the Swiss company Nabalco from mining for bauxite from 300 square kilometres of land excised from the Arnhem Land reserve. In this landmark appeal, designs painted in ochre on two panels illustrating Yolngu law surrounded typed documents expressing their concerns. The appeal was unsuccessful — but influenced events that led to a referendum in 1967, resulting in constitutional change and recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The discovery of illegal fishing and the desecration of sacred waters was the catalyst for 47 Yolngu artists to paint 80 barks that were shown in a national tour and featured in the publication Saltwater: Paintings of Sea Country: The Recognition of Indigenous Sea Rights.12 These powerful and beautiful paintings and the rich, poetic narratives they encode were first exhibited in Canberra in 1999. They trace the journey to recognition of Yolngu legal rights over their saltwater lands in the successful Blue Mud Bay Case.

Yalangbara c.1960

- MARIKA, Mawalan 1 - Artist

- MARIKA, Wandjuk - Artist

- GANAMBARR, Larrtjanga - Artist

- MARIKA, Nurryurrngu - Artist

- GANAMBARR, Mowarra - Artist

- GURRUWIWI, Mithinarri - Artist

- DHAMARRANDJI, Gungguyama - Artist

- YUNUPINGU, Munggurruwuy - Artist

Gan'yu (Stars) 2007

- YUNUPINGU, Gulumbu - Creator

Diane Moon is former Curator, Indigenous Fibre at QAGOMA.

Endnotes

- Madarrpa artist Djambuwa Marawili, personal correspondence, undated.

- Traditionally, materials such as resin, sap and egg yolks were used as glue or binding agents. Wally Mandark (1915–37) is an example of an artist who continued to prefer using the sticky juice of the tree orchid (Dendrobium affine).

- Cherie Beach, ‘Arnhem Land art “detectives” helping discover who painted these priceless works’, ABC Radio Darwin, 5 June 2022, , viewed July 2022.

- Nicholas Rothwell, ‘The Collector’, The Monthly, October 2007, viewed July 2022.

- Rothwell.

- Rothwell.

- ‘Buwayak’ first came to public attention in a 1983 solo exhibition of abstract bark paintings by Gudthaykudthay at the prestigious Gary Anderson Gallery in Potts Point, Sydney. Gudthaykudthay’s Badurru in Gunyungmirringa landscape no. 2 1983, acquired from this 1983 show, is included in ‘Transitions’.

- Sandra Le Brun Holmes, Yirawala: Painter of the Dreaming, Hodder & Stoughton, Sydney, 1992.

- Michael Fitzgerald, ‘Papunya to Paris: Arhhem Land artist John Mawurndjul, Paris, Sept. 2005’, TIME, 22 May 2006, cover page.

- Michael Fitzgerald, ‘Rock Spirits’, TIME, 7 October 2004, viewed July 2022.

- Terry Smith, ‘Marking places, cross-hatching worlds: The Yirrkala Panels’, e-flux journal, issue 111, September 2020, viewed July 2022.

- Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre, Saltwater: Paintings of Sea Country: The Recognition of Indigenous Sea Rights, Isaacs Publishing, Neutral Bay, NSW, 1999.

Digital story context and navigation

TRANSITIONSExplore the story

About this page

Related resources