Gone Fishing

By Katina Davidson

Artlines | 1-2023 |

‘Gone Fishing’ presents Indigenous Australian artists’ works from the QAGOMA Collection that affirm the cultural, social and recreational activity of fishing — an interest that transcends boundaries in Australia and abroad.

Mawalan 1 Marika / Rirratjingu/Miliwurrwurr, Dhangu people / Australia, 1908–67 / Wandjuk Marika / Rirratjingu people / Australia, 1927–87 / Larrtjanga Ganambarr / Ngaymil/Dathiwuy people / Australia, c.1932–2000 / Nurryurrngu Marika / Rirratjingu people, Yolngu / Australia, unknown–1979 / Mowarra Ganambarr / Dathiwuy people / Australia, c.1917–2005 / Mithinarri Gurruwiwi / Galpu, Galwurr, Dhangu people / Australia, 1929–76 / Gungguyama Dhamarrandji / Djambarrpuyngu people / Australia, c.1916–70 / Munggurruwuy Yunupingu / Gumatj people / Australia, c.1907–78 / Yalangbara c.1960 / Purchased 2003 with funds from the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Appeal and the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Grant / Collection: QAGOMA / © The artists

Sea rights: Politics, lore and custom

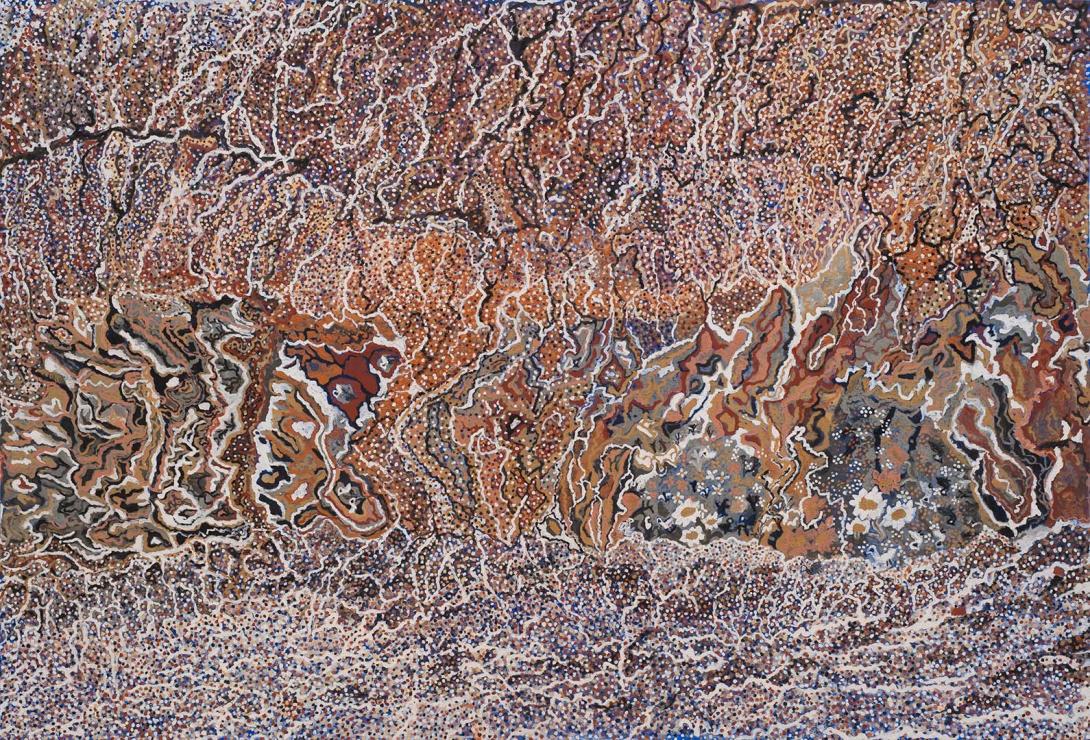

Waterways and seas are important resources that have sustained communities for millennia, and their existence carry important stories of creation. In the past century, the ‘ownership’ of such parcels of water — and the resources that are found in and below them — has been debated. This exhibition responds to current topical discussions around rising and warming seawaters, destruction of cultural sites, the contamination of waters and the struggle by Traditional Owners to have power to care for their Sea Country under Native Title law. These themes can be seen in works such as Mabo Case 1 and 2 2017 by Gail Mabo, bloom 2009 by Judy Watson and an intergenerational Yolngu collaboration.

The exhibition opens with the collaborative bark painting Yalangbara c.1960, which asserts the Yolngu people’s responsibility to protect the land and sea against harm. As Diane Moon (former QAGOMA Curator of Indigenous Fibre Art) writes:

Lead artist Mawalan Marika #1 was one of the main contributors to the famous, monumental 1963 Yirrkala church bark panels and, in response to the Swiss company Nabalco mining for bauxite around Yirrkala, he became an activist for the protection of his land and culture. Yalangbara is a rare collaborative bark painting dated c.1960, which makes it an earlier version of these magnificent ‘Church Panels’ of 1962–63. Mawalan #1 painted a major component of the landmark 1963 Bark Petition presented to the Australian Parliament in Canberra in an attempt to have the mining operations stopped. Mawalan was also one of the original plaintiffs in the historic Gove Land Rights case. Though a decision against the Yolngu claim was ultimately handed down in 1971 (after Mawalan’s death), their actions eventually had positive benefits, paving the way for the future successful Mabo and Wik Native Tile claims.1

This historical work provides a strong political and artistic foundation for the contemporary works that follow in its footsteps. Each artist’s work speaks to their individual community’s position in these long-heralded debates — against destruction, pollution and the effects of climate change — that show no signs of slowing.

Traps, tackle and gear

From inland freshwater regions and out to the ocean and islands of the Torres Strait, there are a host of specifically engineered tools and methods for catching a feed. These multifunctional objects are represented through cultural objects, paintings, sculptures and installation. The artworks in this section speak to the practical nature of fishing and include a range of spears, canoes and nets by artists such as Bernard Singleton Jr, Yvonne Koolmatrie, Jack Maranbarra, Elisa Jane Carmichael and Rex Greeno. An installation of woven fish traps from the Maningrida region (Arnhem Land, NT) illustrates regionally specific techniques that were perfected by hundreds of generations of the artists ancestors, specifically made for each environment and species of food source.

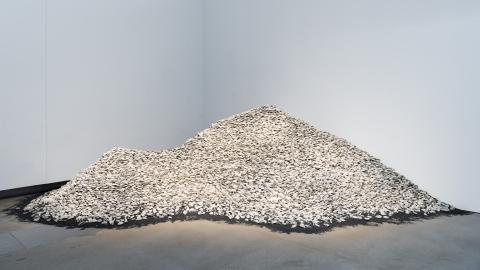

The late Mandandanji artist Laurie Nilsen’s Baited 2010 and Once were Fishermen I and II 2014 were the inspiration for this survey of fishing practices. These sculptural fish and yabbie traps cleverly use discarded materials to create functional devices. Upcycled pedestal fans, chicken wire and Sunshine soap were, according to the artist, all you needed to catch a feed — if your traps didn’t fill with debris from congested waterways first. As Sophia Nampitjimpa Sambono (Jingili), Associate Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, writes:

Laurie Nilsen’s approach to his art and materials he used are a product of his upbringing in south-western Queensland. Life on rural properties necessitates a willingness and ability to ‘do it yourself’ and practice sustainability in ‘making do’ with materials at hand. Nilsen employed this deft ability in Once were Fishermen I — invoking ancient knowledge in his fish trap design while providing a pointed political and environmental commentary through its barbed wire and mesh construction and catch of the debris of contemporary society. The ‘catch’ inside the trap consists of rubbish and debris collected by the artist at the mouth of the Brisbane River — plastic bottles, discarded toys, abandoned thongs, plastic fish, and a tin lid inscribed with ‘come in spinner’ (referencing an earlier work) — all tell of a disposable lifestyle, overrun with plastic, and endangering the natural environment.2

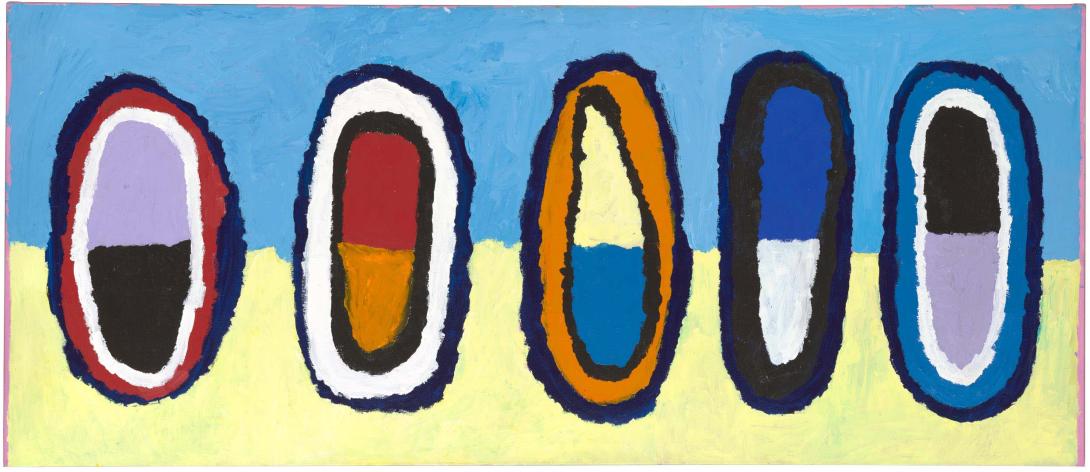

Painted recollections of the site-specific fish traps built into the tidal zone, and sculptures that are conveniently fashioned from found items, further demonstrate the ingenuity and beauty of fishing tools. Yvonne Koolmatrie’s eel traps of 2007 are created in the traditional method using sedge grass and river rushes, included in this context to celebrate their sculptural forms. Diverse sculptural works created with traditional techniques and materials are joined by those that reflect ceremonial aspects of culture by Ken Thaiday Snr. His Fish trap land and sea dari headdress 2010 are articulated handheld dance machines that take on stories of his island home of Mer through movement in choreographed routines. They are complemented by paintings by senior artist Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori — who locates fish traps built into the low tideline on her father’s Country — and Regina Pilawuk Wilson who meticulously charts the geometric forms of woven netting onto canvas, illustrating a delicate and geometric perspective to these sturdy objects.

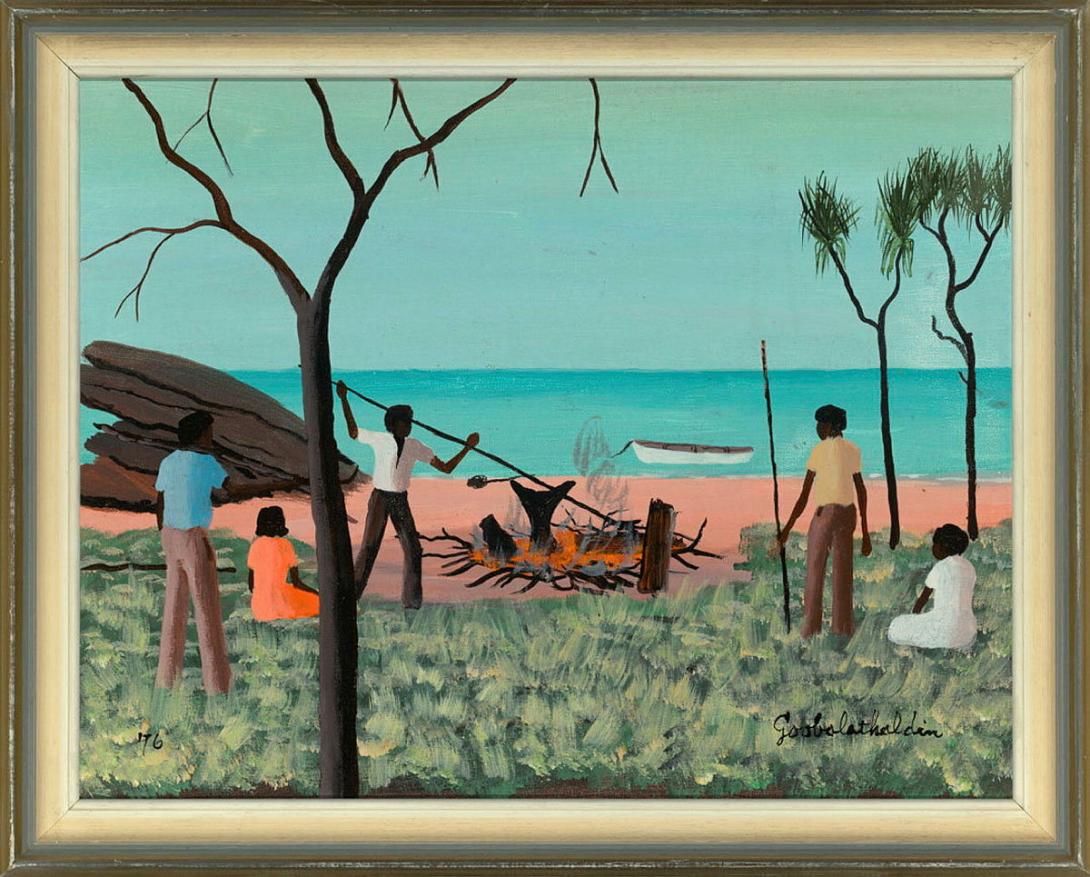

Spearing dugong 1971 and Cooking dugong 1976 are two important paintings belonging to a lesser-known period in the career of Queensland Aboriginal artist Goobalathaldin Dick Roughsey. Best known for his depictions of traditional stories, these two intimate figurative paintings capture candid moments of life on Lardil country. Here we can see community members engaged in distinct hunting practices on Country. Spearing dugong 1971 depicts men spearfishing by traditional methods in shallow waters, while Cooking dugong 1976 presents men and women gathered around a fire on the beach, cooking their dugong feast, their small boat moored in the shallows. As a pair, these works illustrate the strength of Lardil dugong-hunting practices over time, depicted here as continuing before and after the arrival of Missionaries to the region.

Along the shoreline

The final theme of the exhibition celebrates the leisurely and recreational nature of fishing. The featured artworks take in the quiet contemplative moments, such as capturing the splash of a paddle in Wanyubi Marika’s Mumutthun (Paddle splash) 2006; the colours and wonder that can be explored at an exposed reef at low tide in Naomi Hobson’s When the Tide Goes Out 2018; and memories of special seaside places around Aurukun in far-north Queensland, shared by Mavis Ngallametta in her large-scale painting Ngak-pungarichan (Clearwater) 2013.

In a celebratory display, these artists from across the country share many waterside moments throughout history. For thousands of years, the waterways and seas in this country have sustained life and carried important stories of creation. Their protection continues to fall to us, so that we may enjoy — either literally or figuratively — the unifying cultural, social and recreational activity of fishing.

Katina Davidson (Yuggera/Kullilli), Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, is the curator of ‘Gone Fishing’ (20 May 2023 – 21 January 2024 | Gallery 3.5).

Endnotes

- Diane Moon, acquisition essay, 2003.

- Sophia Sambono, acquisition essay, 2021.